Data analysis: Investment costs have been held up as the straw man of DC investment, but how important are they to member outcomes?

But up to this point, politicians’ focus had been on getting the industry to define and deliver ‘good’ member outcomes – an even greater challenge in this new environment.

Conversations around value have centred on charges, in part because they can be “immediately influenced”, in the words of Alan Morahan, head of DC consulting at consultancy Punter Southall.

There is no evidence that higher charges can ‘buy’ more sophisticated investment strategies that deliver superior performance

Pensions Institute

Put another way, charges are a visible and tangible way to gain traction on the more complex issue of value.

Pensions minister Steve Webb confirmed in March that a cap of 0.75 per cent on default funds of schemes used for auto-enrolment would come into force from next April.

As the impact of the Budget focus beds in, the conversation will inevitably return to what price these product innovations can be delivered at, and whether their results constitute value.

For The Specialist full report on DC investment, click here for the PDF.

The main objections to a cap from many providers and consultants are as follows:

Many qualifying schemes are already operating well below the charge cap;

A cap would stifle innovation and could block members from sophisticated investments that could deliver better returns;

High charges were predominantly a problem for legacy schemes set up prior to 2001, so why throw the baby out with the bath water?

Others, meanwhile, have pointed to the fact that even incremental increases in charges can have an exponential impact on savers’ pot sizes.

But there is also concern that taking a tunnelled view of charges has diverted focus from other, perhaps greater, influences on retirement incomes such as contributions.

A raft of research last year sought to establish exactly to what extent charges affect member outcomes. This included a government survey published in October, which among its findings noted advisers cannot agree on what instances it would be worth paying above the cap.

Trust-based schemes were found to have an average annual management charge of 0.75 per cent – in line with the cap – while contract-based schemes are averaging 0.84 per cent.

But what difference does a few basis points here and there really make to savers’ returns? Is there even a correlation between what members and employers pay, and overall performance?

In November, the Pensions Policy Institute carried out research to establish where the balance lay in terms of charges versus outcomes in DC schemes.

It found that actively managed strategies, such as low-volatility and diversified growth, are judged by some employers as offering better value for money despite the higher charges.

For The Specialist full report on DC investment, click here for the PDF.

Paul Bucksey, head of UK DC at asset manager BlackRock, says the added costs associated with such strategies offer a viable trade-off. “DC investors may value the additional protections offered by multi-asset or volatility controlled funds versus more volatile, but less expensive forms of investment management,” he says.

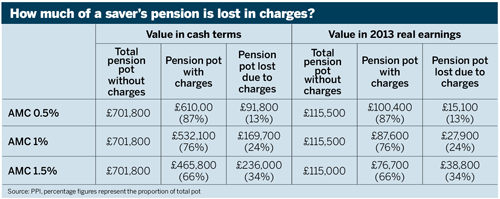

The PPI study showed a member saving from aged 22 to state pension age under a 1 per cent AMC would lose a quarter of their final pension pot to charges (see table).

This assumes the individual has contributed throughout that period and does not account for people who take career breaks or deferred members, so the AMC will continue to eat away at the pot while no contributions are going in. But the government’s pot-follows-member proposals may go some way in alleviating this risk for deferreds.

And active member discounts – often viewed more as a levy on deferred members – were cited as a significant risk to returns, potentially adding around 50bp to the member’s AMC.

The PPI’s report found there are some 10,000 contract-based schemes with AMD structures in place, the vast majority of which (94 per cent) are eligible for auto-enrolment. The government is exploring banning AMDs from 2017.

Either way, the inputs and outputs surrounding charges do not get to the crux of whether those higher fees are actually buying better value for members. In January this year, the Pensions Institute in its VfM: Assesing value for money in defined contribution default funds report sought to gauge value beyond mere cost.

The headline finding was that there was no link between charges and performance. It stated: “While ‘cheapest’ is not synonymous with ‘best’, there is no evidence that higher charges can ‘buy’ more sophisticated investment strategies that deliver superior performance.”

Other performance drivers

The government’s October paper found the biggest drivers of AMCs are scheme size and members’ salaries, meaning in general smaller employers and those in sectors where wages are low shell out more than larger employers – supporting findings by the Office of Fair Trading in its September 2013 report.

What goes in and stays in members’ pension pots will have a significant steer on outcomes, along with investment returns. But while many have flagged low contributions as a major risk, employers have been waiting for the contributions to be phased in, before addressing whether to increase either their own or their members’ contributions.

Governance is also key. Schemes that tend to deliver above-average outcomes relative to contributions are single trust-based schemes and modern trust-based multi-employer schemes, the VfM report found.

Mike Spink, DC pension consultant at Spence & Partners, says regulatory guidance that demands a new value-for-money assessment by trust-based schemes will “elevate charges analysis to the same level as the quality of service received from the various providers”.

Andy Dickson, investment director, UK institutional, at asset manager Standard Life Investments, says the Budget changes has also pushed investment returns up the agenda of factors that have a material impact.

Under the new regime, Dickson says a 90-year-old who starts saving at age 20 and stops at age 60 will find that “10 per cent of wealth was created from contributions, 30 per cent from investment returns up to age 60, and 60 per cent from investment returns after age 60”.

Brian Henderson, senior consultant at Mercer, says the increased flexibility introduced by the Budget now makes good outcomes, and the cost of getting there, even harder to define.

“Is it cash, secured income, or is it variable income – post-retirement earnings or drawdown income?” he asks. “There are different costs depending on which route you take.”

It has been argued that a cap on charges will disincentivise providers from developing new products that could produce better outcomes for members.

Henderson says some larger schemes have been using higher-cost DGFs, many of which could see them breaching the cap.

“The reality is those trustees that adopted these well-diversified funds did so on the basis they felt they would deliver a better outcome for consumers,” he says. “Now they are faced with having to unwind some or all of these funds to keep charges below the cap.”

However, SLI’s Dickson says it is possible for schemes to invest in more sophisticated DGF strategies and keep below the cap, which it achieves by blending DGFs with passive trackers. But he warns: “Time will tell whether and to what extent [the Budget changes] stifle innovation to support the new ‘to and through’ retirement phase.”

A 0.75 per cent cap impinges on many default strategies, even among larger employers, counters Nico Aspinall, senior investment consultant at Towers Watson.

“Passive and static variants of DGFs do exist, but we are concerned that someone does need to review the allocation from time to time and this costs money,” he says.

Aspinall adds that the threat of a further cap reduction to 0.5 per cent means “the scope for innovation within defaults has been pushed back dramatically”.

Performance is as much down to managing risk as it is overall returns, says Henderson, but costs tend to focus only on the latter.

The scope for innovation within defaults has been pushed back dramatically

Nico Aspinall, Towers Watson

Aspinall agrees; performance is not solely defined by the overall return, but the timing and nature of return-seeking. Growth will be achieved through equity investing and diversification, but attention must be paid to risk-adjusted return, he says.

“This will be suitable for many younger members but as they approach retirement we should be talking about risk-adjusted return, with risk measured relative to the member’s needs at retirement and the degree of security their portfolio offers them,” he adds.

Martin Freeman, director at consultancy JLT Employee Benefits, warns that funds labelled as low risk can be a misnomer and could lead to poor returns.

“Locking into a ‘low risk’ cash or bond fund early in a person’s career could lead to substantial missed returns by the time the person retires,” Freeman warns. “That means poor member outcomes.”

For The Specialist full report on DC investment, click here for the PDF.

The interplay between charges, contributions and governance is among the factors that will drive performance and value. Charges on their own can cynically be viewed as a simplistic inroad into the more complex route towards good outcomes.

But they do offer an easily identifiable yardstick for members that could help garner faith in the industry, during a time when politicians gamboling across the pensions landscape has muddied what for many is an impenetrable subject.

JLT’s Freeman notes: “Consumers care about charges. Unless they understand how much they are paying and for what, we will not be able to earn their trust and talk to them about the other things that matter in getting them the best outcomes we can.”

Maxine Kelly is a reporter at Pensions Expert