Each day brings further news of the spreading coronavirus and its impact on communities and economies. Lockdowns now affect more than one third of humanity and we wonder what may come next.

Among all this there are occasional positive signs, notably from China. Incremental Covid-19 cases there have declined significantly, with most now imported from abroad. People remain very cautious, but life has started to return to normal. Even the shutdown of Wuhan – the original emergence of the virus – is being eased.

The unique way the Chinese system operates has greatly helped with managing the virus outbreak. Western countries do not have the technological capability or social compliance to implement such extreme lockdowns.

As a result, Chinese equity indices have recently significantly outperformed global markets, both developed and emerging. In addition, Chinese investment managers have continued to outperform during these turbulent markets.

Centralised management means that the country can achieve objectives that are nearly impossible for others – for example, around infrastructure or regulatory changes – but policy mistakes do happen and can be costly. The management of financial markets is no exception

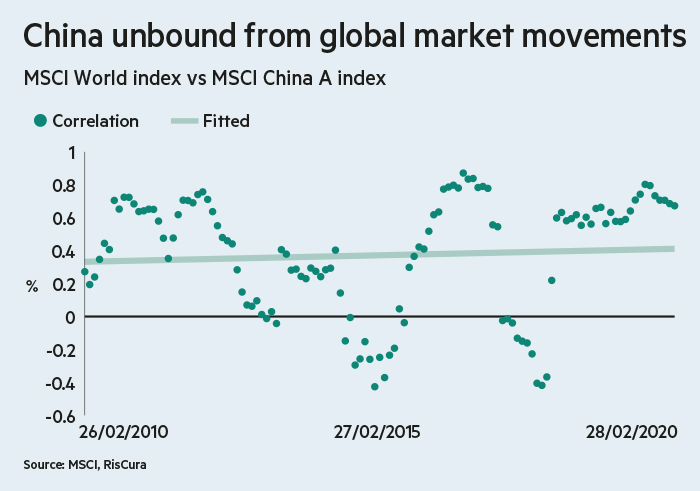

In short, China offered material diversification benefits recently, just like it did from 2007 to 2009. The low correlation of Chinese equities with other regions is well documented.

But why is this? In our opinion, a fundamental reason is its unique shareholder base, which has different motivations to shareholders in other countries, both in developed and emerging markets.

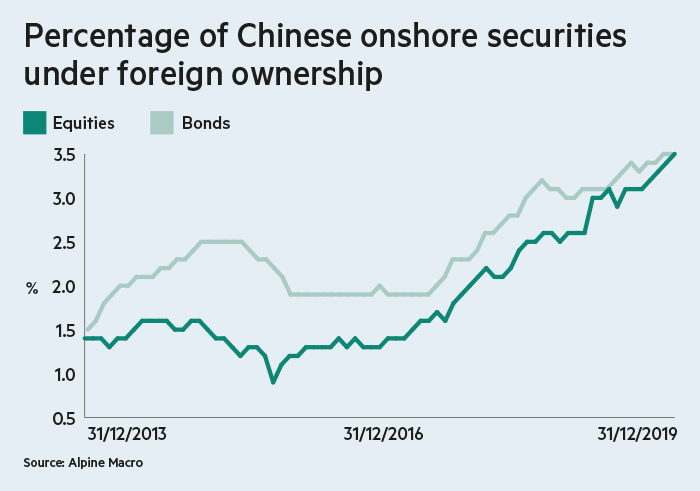

The following chart shows the foreign ownership of mainland China securities. This has increased significantly but remains barely above 3 per cent of market capitalisation. The remaining 97 per cent are local shareholders who are largely restricted from investing offshore; they have different objectives to western investors and their perception of risk differs too.

We believe this will change over time as foreign shareholding increases. However, it depends on many factors such as the pace of reform of Chinese markets, adoption by global asset owners, index providers and fund managers.

Market pricing is less efficient

For now, Chinese A-shares are not reliant on the same global flows as other equity markets. There is an almost consistently high positive relationship between developed markets and emerging markets, whereas the relationship between Chinese A-shares and developed or emerging market shares is very inconsistent and negative at times (see chart below).

Furthermore, almost half of Chinese shareholders are retail investors. Many, if not most, local asset managers are still guided by short-term performance. This means that prices are driven far more by sentiment and speculation than the underlying fundamentals of companies. This in itself creates a different pattern of returns, albeit with higher volatility.

Next, the Chinese state attempts to manage all aspects of the local economy. We recognise this as a double-edged sword: centralised management means that the country can achieve objectives that are nearly impossible for others – for example, around infrastructure or regulatory changes – but policy mistakes do happen and can be costly. The management of financial markets is no exception.

Just as many of the world’s investment policies are dictated by the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank, the Chinese are affected by what their central bank does.

Over the past decade, China has implemented both extremely tight and loose monetary and fiscal policies in pursuit of a stable economy. This has caused shorter and sharper market cycles that can be completely unrelated to what is happening elsewhere in the world. Unconventional measures may also be used, like influencing the activities of state-owned asset managers to prop up stock markets.

When mistakes are made, having ‘executive control’ allows the Chinese government to respond to policy mistakes quickly. Examples include the circuit-breaker mechanism and stock suspension rules implemented in 2015-16, and economic deleveraging in 2017-18, which were implemented to correct earlier policy errors.

The other global superpower

The last pillar, perhaps most important in the longer run, is the Chinese economy itself, fed by its large population. There are more than 5,000 Chinese companies listed on the mainland and internationally that benefit from this large population, which is well connected through both technology and roads and railways, with a fast-growing middle class, a steady trend towards urbanisation and with that substantial domestic consumption.

Many of those 5,000 companies only focus on domestic business and have little exposure to overseas markets. The vast domestic market presents them with incredible growth opportunities.

All this means that China can press ahead independently and impact the world in a way that currently only the US can.

A recent conversation with a Chinese asset manager revealed just how the consumer is increasingly the main driver as opposed to exports, which now only account for 17 per cent of China’s GDP. The average youngster has not wanted to work in a factory for more than 10 years.

JD.com and New Oriental Education & Technology Group, representing China’s new economy, recently announced the recruitment of 20,000 delivery riders and 5,000 teachers, respectively.

Investors may not be aware of quite how differently China performs – both its economy and financial markets. Every investor seeks diversification, and we believe that China has much to offer to improve the risk profile of an equity portfolio. Ignoring it, or lumping it in with the emerging markets allocation, leaves a tasty free lunch uneaten at the table.

Lars Hagenbuch is an investment consultant at RisCura