Feature: Three-quarters of UK employees expect to be poorer in retirement than their parents, reversing the apparent laws of financial progress.

A month into 2016 the nation finds itself at an impasse; the Bank of England has revised-down growth, houses in Peckham cost £500,000 and the risk of a Brexit looms large. Somewhere along the way, financial progress trundled off course.

Progress is wrought around visions of striving onwards and upwards from our humble beginnings towards a future that is better than yesterday.

What should have been a continuing healthy pensions system becomes a one-off offer for a generation that won't be repeated

David Willetts, The Resolution Foundation

A belief in progress often includes the conviction that we will exceed our parents’ wealth and achievements during the course of our own lives. But for many young people today, hopes and dreams of outdoing their parents are dissipating fast.

Progress reversal

In 2016 young people are tied to a very different mast compared with the generations that preceded them. This is the generation that pays tuition fees, may never own a home and has no pension ‘promises’ – posing new challenges to UK employers and the pensions industry.

The natural order of progress is also upturned when it comes to retirement expectations. Nearly three-quarters (71 per cent) of UK employees believe they will be less comfortable in retirement than their parents’ generation, research by consultancy Willis Towers Watson has found.

David Willetts, executive chair of independent think-tank the Resolution Foundation and author of ‘The pinch: how the baby boomers took their children’s future – and why they should give it back’, says young people are right to be worried about what kind of pension they will be retiring on.

“Pensions and housing are the two most vivid examples of how one generation has ended up taking all the spoils and leaving the generation after them in the lurch,” he says.

With little regard for the long term, baby boomers have welcomed successive rounds of legislation securing “enormous pension promises”, Willetts adds – promises that many companies are no longer willing to honour.

“What should have been a continuing healthy pensions system becomes a one-off offer for a generation that won’t be repeated.”

Financial concerns

In the absence of past promises, young people’s fears could play out as inevitable truth, with the future of UK retirement prospects stored up in defined contribution arrangements where individuals bear all of the risks and must take action to increase contributions to meaningful levels.

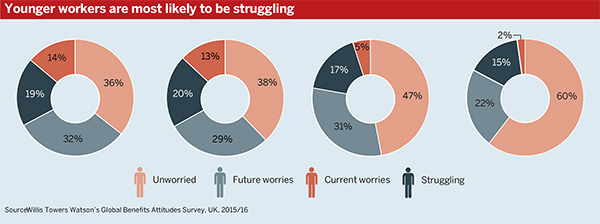

Willis Towers Watson’s study shows a third of UK employees in their 30s are either struggling or have concerns about their short-term financial obligations taking up cash that would otherwise be steered into a pension arrangement.

At the other end of the spectrum, two-thirds of professionals over age 50 – many of whom will have a proportion of DB accrual – said they were “unworried” about their financial position.

The UK has seen significant economic recovery and rising salaries, and inflation has been relatively low since 2013 when the survey was last conducted, says Minh Tran, senior consultant at Willis Towers Watson.

But financial priorities continue to segregate different cohorts of workers, he says. “Saving for retirement – particularly for the younger age cohorts – is not their top priority. They’re struggling the most with their financial situation.”

Short and medium-term strains on monthly budgets, including rising living costs, student debt, housing costs and saving up for a deposit, make it increasingly difficult to make meaningful contributions towards retirement savings.

All too often younger cohorts fail to take advantage of generous contribution structures offered by many employers who choose to exceed the levels required under auto-enrolment legislation, says Tran.

“The data we have on FTSE 350 shows… although those generous contribution structures are on the table available, those particularly in the younger age cohorts don’t take up the employers’ maximum contribution rate,” he says. “They have more immediate financial priorities.”

Employer action

Companies have to consider how to meet the short, medium and longer-term financial needs of their employees in benefits packages, Tran says.

“It’s not just a pensions issue, it’s broader than that; it affects employees of all ages – not just those that are thinking about retirement.”

An increasing number of employers are implementing strategies that allow additional DC contributions to be used more flexibly; one in 10 (11 per cent) FTSE 350 companies allow employees to take some of their DC funding as cash, or permit investment of funds via an alternative vehicle – either a corporate Isa or investment account.

In an age where the lines between work and life are increasingly blurred, many young people will look to their employer for help and guidance.

For younger generations, keep it simple: make the most of matching [contribution structures], put your money in and let it compound

Lydia Fearn, Redington

Lydia Fearn, head of DC and financial wellbeing at consultancy Redington, says providing employees with clear benchmarks and achievable goals can help drive engagement with retirement savings.

Messages must be easy, accessible, social and timely, she adds, and should be delivered in the wider context of financial pressures.

“For younger generations, keep it simple,” Fearn says. “Make the most of matching [contribution structures], put your money in and let it compound.”

Policy drivers

The Work and Pensions Committee launched an inquiry into ‘intergenerational fairness’ last month, to assess growing concerns that the UK’s older demographic is accumulating wealth at the expense of younger generations.

The review will compile evidence on the sustainability of current distributions of income, wealth and public expenditure and consider the way recent developments in legislation and policy have structured intergenerational inequality.

The Resolution Foundation’s Willetts says the review is a welcome development, but the challenge remains for pension policy makers to seek out a less expensive, less ambitious pensions promise to provide a middle ground for savers.

“There are a whole host of ideas, from collective DC… defined ambition schemes, [to] career average revalued earnings and hybrid schemes,” he says.

“That middle ground is where the future lies; something a bit better than pure DC but nothing like as costly for companies as full final salary.”

Acknowledging the widespread closure of corporate DB schemes across the country, Willetts insists the middle ground will come back onto the corporate agenda as older workers struggle to transition out of the workplace as a result of inadequate savings levels.

“Companies will find themselves having to make discretionary payments to get people to leave. Then we will think, ‘Why don’t we have some kind of framework for these rather than just being completely ad hoc?’,” he says.

“At that point, the case for a regulatory... and tax framework that saves us some kind of hybrid pension will be very strong indeed.”