In the first DC Debate of 2017, eight defined contribution specialists discuss the pros and cons of illiquid assets, traditional indices and smart beta strategies.

How can DC members profit from illiquid assets and what are the risks?

John Reeve: Instinctively it feels appropriate for DC members to benefit from the liquidity premium available for those with a long investment horizon. However, any solution is likely to have to rely on the possibility of surrender penalties, which are unlikely to be acceptable, however economically justified they may be.

I suspect any attempt to offer such a product will put off more people than it will benefit. It may be that the old maxim of ‘keep it simple’ applies and these investments will never be accepted by the mainstream.

Illiquid assets come with complexity – trustees will need to get comfortable with mismatches in pricing, long lock-in periods and generally higher fees, something DC members are not used to

Laura Myers, LCP

Whether we can come up with something for the sophisticated investor, who can weigh up a surrender penalty against the benefit of higher returns, will depend upon whether regulation can allow such innovation.

Helen Ball: Illiquid assets could be attractive for DC members looking to invest over the long term. There is no regulatory barrier to holding illiquid investments, but there are some practical obstacles. DC investments are subject to short-notice, individual member decision-making. They need to be accessible outside the normal run of events. These events will trigger a need to liquidate the member’s units, which is at odds with the principle behind such assets.

To manage this, trustees can use collective investment schemes. However, this could affect the investment characteristics of the asset and limit the value of the illiquidity premium. Trustees therefore need to understand the likely needs of their members when considering this as part of their investment strategy.

Simon Chinnery: Given the long-term nature of retirement saving, DC and defined benefit face similar challenges. DB schemes have been successfully accessing illiquid assets for years. DC schemes, given governance and regulatory constraints, have been slower to adopt.

The benefits of better risk-adjusted return potential have been well established in the DB and endowments space, as have those of diversification. In DC, however, exposure to these assets is best managed within multi-asset funds, where economies of scale and investment skill can be employed to overcome the ongoing challenges around managing daily liquidity.

Laurie Edmans: DC members should be able to take advantage of the length of time that they have to and beyond retirement, to not have to be artificially constrained by the marketability of assets.

Alistair Byrne: The additional diversification and potentially higher risk-adjusted returns from illiquid assets can improve the efficiency of DC default funds. Typically, this will be as part of a multi-asset or target date fund, where an allocation to illiquids is balanced with listed investments to provide the required liquidity to members.

The higher management cost of many private market investments is an issue, but schemes may be able to budget for a 10 per cent to 20 per cent allocation to illiquids alongside a lower-cost index fund.

The main risks are around managing redemptions; trustees and sponsors need to be comfortable with the process for rebalancing and/or gating.

Laura Myers: The rationale for holding illiquid assets is the expectation that they will deliver growth beyond that of more liquid assets. DC pensions typically invest in quoted liquid markets due to the daily liquidity requirements of many platform providers.

If members invest in illiquids, they are potentially taking on a higher level of risk. Particularly for younger members, the long-term potential gains of illiquids are needed to help achieve good retirement outcomes.

However, illiquid assets in DC come with complexity – trustees will need to get comfortable with mismatches in pricing, long lock-in periods and generally higher fees; something DC members are not used to.

Andy Dickson: There would appear to be a strong case for DC investment strategies to include exposure to illiquid assets, due to the additional diversification and uncorrelated sources of return they can add, as well as outperformance compared with listed assets.

However, investors are unlikely to be able to access their capital for periods of time. This can clearly present risks if for example there was a mismatch of cash flow. If DC members are looking to access their savings en masse and there is insufficient liquidity at scheme level then that would obviously create problems. That said, this scenario is unlikely if allocations to illiquid assets at scheme level are relatively modest, for example less than 10 per cent.

Another risk is that trustees need to be comfortable with the valuation methodology and frequency for their holdings, so that it can be presented to members.

Neil McPherson: Illiquid assets are being increasingly used by DB schemes to enhance returns by giving up the liquidity premium on the premise that they are not looking to buy and sell, rather progress against their ‘journey plan’.

DC members have a journey plan too – to maximise portfolio growth, within acceptable risk, before freedom and choice decisions kick in. Illiquid assets could really help here, particularly in the first 10 to 20 years of the growth stage.

Their usage is hamstrung by the requirement for daily liquidity, which is largely unnecessary in the growth stage. The infrastructure of DC administration is built around daily liquidity, so any change facilitating investment in illiquids would not be trivial.

What are the problems inherent in market cap weighted indices, and what does this mean for DC savers?

Reeve: The biggest problem for market cap weighted indices is their tendency to buy stock as it gets expensive and sell when it is cheaper. They also lead to a potentially overly concentrated portfolio.

However, their ubiquitous influence on mainstream media and public perception means any attempt to move away from such indices will have to fight the fact most people will compare performance with overly quoted market cap weighted versions.

Even though performance is likely to be better in the long term, one must also understand the fear factor that drives short-termism and will push people towards what they see as the norm.

Ball: The ability of market cap weighted equity indices to provide average market returns for low fees, as well as their liquidity and low turnover, means they continue to dominate the market for equity index products, particularly those used by DC schemes.

While reflecting the performance of stocks in proportion to their market capitalisation is a useful tool for measuring the general health of the economy, their reflection of short-term market movements may not represent the best means of providing a risk-adjusted return for some long-term investors.

As trustees search for long-term and sustainable investment return, the use of alternative approaches that reduce the concentration risk inherent in market-cap weighted funds could increase.

I am more wary of people offering smart, expensive solutions to eliminate the risks than of the downside risk of following an index

Laurie Edmans, Trinity Mirror Trustees

Chinnery: There are several well documented challenges when it comes to investing in market-weighted indices. These include costs, market timing and exposure to sector biases.

Before costs, investors receive market returns, while after costs they receive a return lower than the market. By how much depends on the market and the manager.

Unintended biases to certain industries and sectors, meanwhile, can leave investors overly exposed, either domestically or internationally. Equity market cap exposure may be therefore desirable from a return point of view, but less so from a risk management perspective.

Edmans: The problems with market cap weighted indices arise from buying the bad, along with the good. Index constituents changing can also present problems. They can only really work where the market is large enough for the index to be valid.

For DC savers, it is a choice between well known indices with these disadvantages but with the virtual certainty that you will not underperform against a benchmark which may not be optimal but from which the return is not likely to be miles away from what the saver expected, and low costs.

I am more wary of people offering smart, expensive solutions to eliminate the risks than of the downside risk of following an index.

Byrne: Market cap weighted indices are a well-established and straightforward means of getting exposure to the main asset classes and have served DC investors well.

However, in some cases there may be scope to improve risk-adjusted returns by adopting alternative weighting schemes. For example, in fixed income there are obvious reasons for concern with an index having its highest weightings in the most indebted bond issuers. Smart beta strategies have the potential to provide better diversification.

Myers: Market cap indices give a higher allocation to those companies deemed large, but this is not necessarily a good indicator that a stock will do well. Consequently, market cap indices can be prone to asset price bubbles and be at risk of excessive concentration. Within the FTSE 100 UK equity market for example, roughly 30 per cent of is made up of only five companies.

For DC savers, a lack of diversification across companies is concerning and can lead to increased volatility in their savings – and this is leading to many schemes reviewing how their equities are managed.

Dickson: If there is a large price move of the largest constituents of a market cap weighted index, this will have a corresponding large impact on the value of the index. This overweighting toward the larger companies can present a distorted view of the market.

What this means to the DC member is they can experience greater volatility and potentially have an overweight exposure to some sectors, creating concentration risk.

A simple golden rule for investing is to spread risk, which can be achieved by having genuine diversification. It is about getting the right balance between risk and reward. If you end up reliant on the movements of indices that are market cap weighted, this may for some just be too risky.

McPherson: While market cap indices are readily communicated and cheap to build and track, their pitfalls are well documented, notably their propensity to facilitate asset price bubbles and their inherent concentration risk.

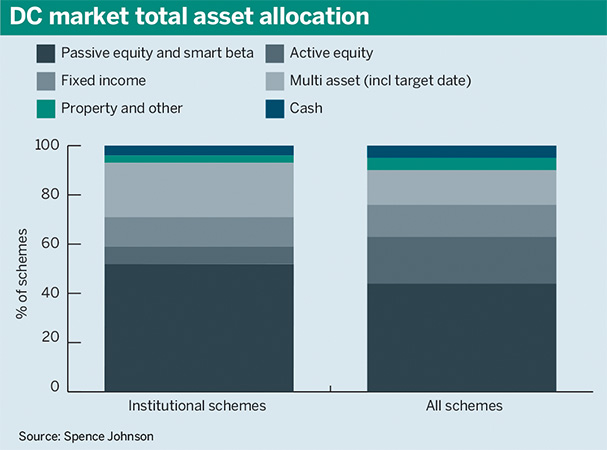

The DC investor is likely to be vulnerable to these potential pitfalls, as more than 90 per cent of them are invested in the default fund, many of which are built around cap-weighted index funds. Alternatively, they may be invested in benchmark-hugging active funds, which are vulnerable to the same issues.

Fees and the charge cap are clearly a factor in the popularity of such funds in the DC landscape. Factor investing may change it.

What role can smart beta play in DC?

Reeve: This is like my garage asking me what tyres I want on my car. Like most people, I wouldn’t know the difference. Some might be a little safer or may produce slightly better miles per gallon. I will never know. I trust my garage to provide the most appropriate. Do I want a smart beta fund? I just want the fund that is best for me.

Anything that offers higher net returns must have a beneficial effect, all other things being equal. However, that phrase, all other things being equal, is a big caveat. If the creation of investment vehicles that offer smart beta confuses or complicates the process for DC savers then it will do more harm than good.

Ball: Smart beta tends to cost less because there is less day-to-day decision-making for the manager, but it also has higher trading costs than traditional passive management.

It has become more popular in DC schemes recently in the form of factor-based investing, which enables trustees to make a decision about what is in the best long-term financial interests of their members, taking for example environmental, social and governance matters into account.

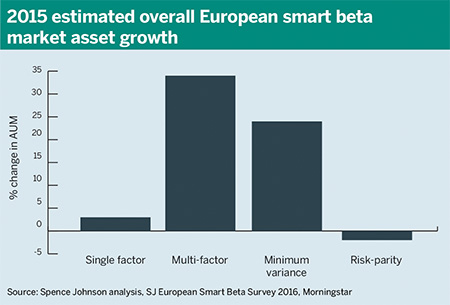

Chinnery: For DC members, the benefits of using a smart beta approach can be to reduce costs, enhance returns, reduce risk and provide diversification.

Academic evidence certainly shows that tilting a traditional market-weighted index with core factors (such as value, low volatility, quality and smaller size) can add value over the longer term. For the majority of DC savers these strategies are best accessed via a default fund.

Academic evidence shows that tilting a traditional market-weighted index with core factors can add value over the longer term

Simon Chinnery, LGIM

Edmans: I struggle to see smart beta other than a particular flavour of active management. There is nothing wrong with it as long as people appreciate what they have.

In theory, a beta-based fund where somebody eliminates the obvious dogs should be a no-brainer.

Byrne: Smart beta strategies have potential to improve the risk-adjusted returns of DC default funds by offering exposure to market factors that have historically offered higher returns and/or lower volatility than market cap weighted indices.

Smart beta strategies are systematic and relatively low-cost, making them particularly suitable for DC schemes. There is scope to adopt smart beta in the lifecycle or target date glide path, using higher returning but more volatile factors in the portfolios of members further from retirement and switching to lower volatility strategies closer to retirement.

Scheme sponsors and trustees do need to be prepared to tolerate periods of underperformance, in pursuit of longer-term improvements in return.

Myers: Smart beta can provide a middle ground between active and passive management. As a rules-based, systematic approach, it invests in well-tested investment styles expected to outperform over the longer term.

It is also more cost-effective than active management, which can be particularly important in DC when some trustees may find themselves quite restricted from an investment perspective due to the charge cap.

I prefer multi-factor smart beta, which allows DC schemes to tap into part of the excess expected return versus the market, but in a more cost-effective way than traditional active management.

Dickson: Some view smart beta as a way to create outperformance as well as bring some diversification – all potentially at a low cost. Given the fee constraints in DC default strategies, it is easy to see how this type of approach looks appealing.

Given that the smart beta manager will be using a particular style, the DC investor will face the risk of periods of underperformance. An investment process reliant solely on algorithms may well result in periods of high volatility. As a result, smart beta in isolation used in DC may present just too much risk to some members.

McPherson: Smart beta offers an effective and efficient solution to the problems of market cap weighted investing. By dialling down the concentration risk and focusing on appropriate factors, schemes can construct a less blunt default fund, with added sharpness from an absolute return or growth portfolio to complement it.

The problem with smart beta is communication, starting with the awful moniker. It can also be overengineered, looking for spurious precision that adds limited value and increases fees.

It sits as a halfway house between the risks, costs and uncertainties of full-on active and the blunt tool that is market cap passive. A good place to be for many DC investors.

Look out for part 2 next week to read our experts' views on the charge cap, value for money, and the pensions dashboard