Private equity is experiencing a renaissance, but nearly a third of institutional investors may abandon their plans to invest over fears about transparency, a new report shows.

The study, from State Street, shows that almost two-thirds (59 per cent) of institutional investors globally are ready to increase their allocation to private equity over the next five years.

However, 28 per cent have threatened to reduce their allocation if the private equity industry fails to meet their demands for greater transparency.

There is still too much, ‘Heads I win, tails I still win’ in some areas of the private equity market

Daniel Godfrey, Transparency Task Force

Private equity assets under management hit a new high in June last year at $2.4tn (£1.7bn), but there is considerable disquiet among investors, the study shows.

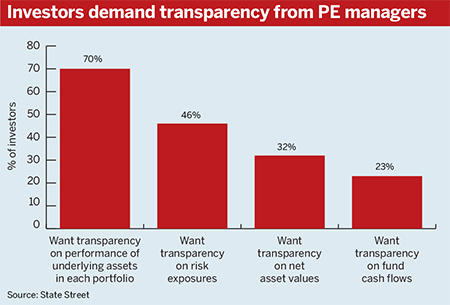

Almost three-quarters (70 per cent) of investors said they want better transparency on the performance of the underlying assets in each portfolio – and the shopping list does not end there.

Nearly half also sought greater read-through on risk exposures (46 per cent), net asset values (32 per cent) and fund cash flows (23 per cent).

The industry is well aware of this demand, said State Street, and only expects the clamour to increase; 83 per cent of respondents said they thought this would be the case.

“It is very clear from our research that failure to provide sufficient levels of transparency increases the risk of driving asset owners away from investing in private equity,” said James Lowry, head of State Street Global Exchange, EMEA.

Private equity has delivered good returns over extended time periods, said Daniel Godfrey, an ambassador of the Transparency Task Force, but there should be transparency over all fees and charges and any carried interest investments made by the managers and the terms on which those interests have been purchased.

He added: “There is still too much, ‘Heads I win, tails I still win’ in some areas of the private equity market.”

‘Different mindset’

But Jonathan Lawlor, a senior investment consultant at Xafinity, said private equity requires a different mindset, and transparency was not useful without an understanding of what the data mean.

“I can calculate a return on equity assets easily, but private equity uses [an] internal rate of return on various vintage years and they may not have invested the full amount of capital allocated.”

So not only do investors have to know how to do the sums, but they will need to have extra strategies for keeping money invested elsewhere in a liquid fund before it is called by the private equity manager.

This requires greater governance, incurs more cost and adds to the complexity of what they are seeking to do.

Lawlor said once a scheme is invested, private equity managers are often very transparent but the underlying investments are not.

“If you’re investing in a coffee chain, how do you know how the coffee sales are going? You are reliant on the data you are given and that needs to be examined closely.”

Interpreting data

The concerns institutional investors have about transparency usually involve a lack of data or detail, but too much data may be worse, as managers can use it to hide bad news or unpalatable truths.

Judith Donnelly, a partner at law firm Squire Patton Boggs, said: “Private equity managers have been sending out documents that state they can act in their own interests and cannot be held accountable.”

Despite meeting their clients’ demands for more detailed information, she said, and in some cases offering good levels of transparency, there is an avalanche of data and it has not always been acted on by schemes, a pattern being repeated elsewhere.

“Transparency is not limited to private equity… There are problems with mutual funds and cash funds as well,” said Donnelly.

“If people are prepared to sign the documents, why should the managers meet them halfway?”

She said this approach, used by private equity and hedge fund managers, is “spilling over” into traditional asset management, and schemes must be aware that if they are seeking greater transparency they have to be prepared to understand the details.

“Ultimately, we really need to do what they did in the food industry,” added Donnelly. “The food industry has opted to have healthier food. We need healthier funds.”