The Isle of Man government last week made clear its intention to further reform public sector pensions on the island, a microcosm of UK schemes struggling to remain sustainable.

The sustainability of ‘gold-plated’ public sector pension arrangements has come under increasing scrutiny since chancellor George Osborne’s push for austerity – a period that has seen corporate defined benefit schemes become an endangered species.

Government decisions on the future of tax relief for pensions in the 2016 Budget, coupled with the end of contracting-out in April, will tighten the screws on public sector schemes and drive further discussion on the long-term affordability of DB.

Employer contribution hike

Long-term sustainability is a major focus for the Isle of Man government, the small crown dependency between England and Ireland, currently assessing proposals for reform of the island’s public sector pensions.

It’s the age-old problem – an older workforce, a maturing scheme; expenditure is going up

Ian Murray, CEO Public Sector Pensions Authority

In its annual budget last week, the Manx treasury called for a “realistic resolution” to address the mounting shortfall in the provision of final salary arrangements across the public sector, the island’s largest employer.

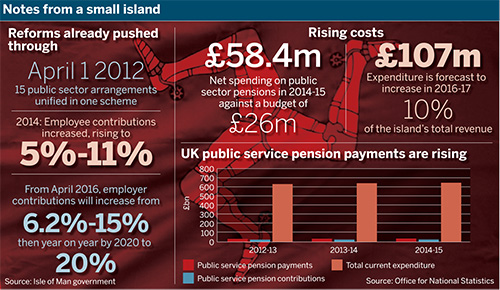

The latest call follows in the wake of a raft of changes already pushed through across the sector – namely the formation of the Government Unified Scheme in 2012, which brought together 15 separate arrangement under one scheme, and increases to employee and employer contribution rates agreed in 2014.

Employers previously contributed 6.2 per cent; from April this year this will rise to 15 per cent, followed by year-on-year rises to reach 20 per cent by 2020.

Net spending on public sector pensions in 2014-15 was £58.4m against a budget of £26m – a shortfall met in part last year by the transfer of £32.2m from the Public Service Employees Pension Reserve.

Expenditure is forecast to increase to £107m in 2016-17 – equivalent to 10 per cent of the island’s total revenue – and under current forecasts the PSEPR will be depleted by 2021-22, at which point any funding shortfall will fall at the door of general revenue.

According to the island treasury’s budget, the majority of current members are within 15 years of their planned retirement age, and until this ‘hump’ of retirees has been replenished by younger members, who will have to work longer before retiring, the island’s cash flow challenge will continue.

Ian Murray, chief executive of the island’s Public Sector Pensions Authority, said expenditure on the scheme has increased over recent years in line with the trimming down of costly public sector services – resulting in a rise in the number of workers taking benefits through early retirement.

Murray added that the proposed employer contribution hike will not go far enough, however, and a working party has recently submitted proposals for benefit changes to government ministers on the island.

Eric Holmes, regional officer for union Unite, said union representatives recognise the need for further reform, given the island’s constitution does not permit borrowing overseas capital to fund shortfalls.

“If nothing changes then yes, the scheme will draw all of the spare cash out of the system,” he said. “Increased contributions haven’t fixed the problem.”

Holmes said a technical advisory group, formed of union representatives and pension experts, has put together a separate proposal to reach a fair and sustainable solution while retaining a DB arrangement.

No system is an island

John Hanratty, partner at law firm Nabarro, said the Isle of Man is an interesting microcosm of wider shifts in the UK, where pressure on the public sector will only increase. Generous accrual rates in UK arrangements, albeit on a career-average basis, may not survive the current regime’s approach to pensions, he said.

“Once they’ve made the reforms will [the government] then turn its sights on the public sector schemes?” he said, noting it might look at things like the 25-year guarantee protecting public sector schemes’ career average revalued earnings structure.

He said as a relatively “blank piece of paper”, the Isle of Man has the opportunity to look further afield and take precedent from collective DC schemes in the Netherlands or cash balance arrangements adopted by a number of UK universities.

“It’s very much just how radical they want to be… something that might not immediately be that palatable but over the longer term gives them the opportunity to sustain a public sector pensions system.”