Property constitutes 7.5 per cent of the Church of England pension fund’s growth assets, but its faith in overseas markets in particular has led it to target a 10 per cent allocation.

Five centuries ago, the Church of England was the country’s biggest landowner. Today, its pension fund is more likely to be seen buying stakes in shopping centres in Guangdong than priories in Sussex.

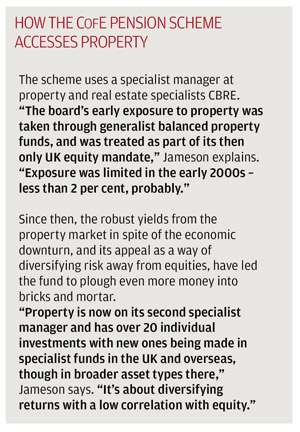

The Church of England Pension Scheme now holds £84.7m – 7.5 per cent of its £1.1bn return-seeking investments – in property, with an ever-increasing fraction going abroad.

Over time, its investors hope to bring that figure up to a tenth of the scheme’s growth assets with upwards of £60m in overseas properties. Pierre Jameson, the pension board’s investment officer, is enthusiastic about overseas property, particularly in Australia, the US and East Asia.

At the moment the scheme holds three-quarters of its property in the UK, but any new investments will push it towards equilibrium; the scheme is considering moving the allocation to a 50:50 split between the UK and overseas.

“We are keen on property currently, but for new money we would look to place it overseas,” Jameson says. “We try to reduce our reliance on the UK because, from the point of view of prudence, it feels wrong when there are so many other opportunities,” he adds, citing better rental and capital growth further afield.

“The Asian market is interesting. We have one fund investing there at the moment, and we expect to set up another one. The feeling is that a lot of the problems in the US property market have worked themselves out as well.”

The scheme is bullish about the prospects of this investment. Property has been one of the scheme’s star performers over the past three years, returning 8.5 per cent a year, well ahead of the 7 per cent benchmark for UK property, underlining its decision to invest more. “We have had a target of 10 per cent [of our portfolio] for about two years,” he says. “Returns have been good.”

How to spend it

Schemes looking to follow the CofE example and invest in overseas property should first note governance issues facing schemes are more sensitive, according to consultants.

How the investment fits into the overall portfolio, whether the manager understands the market thoroughly, the kinds of structures available and the level of liquidity, can be more challenging questions when dealing with less familiar assets.

John Hastings, partner at Hymans Robertson, says schemes should specialise in regions with experienced managers, as the CofE has done, and target specific markets within those regions. “Rather than thinking of property as global property, maybe some managers will launch a southeast Asia emerging economies fund,” he says.

The illiquid nature of the market means it can be much harder to sell foreign properties than foreign equities, for example, and the huge variations between different countries’ legal systems make reliable, specialist expertise a must, Hastings adds.

Schemes wanting to get the most out of this investment may want to consider allocating a sizeable proportion of their portfolio, experts have suggested.

Matthew Abbott, senior real estate researcher at Mercer, says schemes should aim for more than 5 per cent of their portfolio to property, but with a maximum of 15 per cent, as the asset class is illiquid and costly.

He suggests funds with more than £150m to spend could opt for separate accounts, where they will have their own experienced manager and will not have to take the views of other investors into account.

For mid-sized investors such as the CofE, Abbott advises looking at pooled balanced funds, which invest in a broad range of sectors across the UK market and delivered an average 10 per cent return last year; or at multi-manager accounts, where the risk is spread across anything up to 25 managers in different markets, which can include overseas.

The latter can be a cheap way for funds to explore the options abroad, Abbott says.

He adds: “This is not across the board, but many managers have processes whereby they invest in property funds that are higher risk than I feel is necessary.

“They are often highly active portfolios with some development risk and relatively high loan-to-value gearing.”

Staying the course

On the macroeconomic side of investing in property, schemes have been encouraged to keep an eye on the global economy, as property is closely correlated to underlying economic performance.

Mark Meiklejon, a partner at Standard Life Investments, says the company’s fund managers rate property as a worthwhile asset class, encouraging funds to up their exposure, particularly abroad.

Many Asian countries are predicted to blossom for a few years, creating demand and driving up the returns in commercial property, making them an attractive option for schemes looking to reduce their widening deficits.

“We think in the medium to longer term Asia will have a problem with falling demographics, but in the short term it’s a very attractive market,” adds Meiklejon.

The global economic crisis has put the old adage ‘safe as houses’ to the test. Property is one of the riskier asset classes, and overseas property especially so.

But for funds that research the markets diligently and choose their advisers and managers based on their detailed knowledge, there are high and surprisingly safe yields to be reaped.

An investment in property is, as Meiklejon says, one of the purest bets on a country’s fortunes, and the CofE is one of several schemes increasing its stake in the resurgent US housing market and the expanding economies of East Asia.