Derisking and the rise of the secular stagnation thesis – that interest rates might remain depressed as growth rates struggle to gain momentum – contributed to increased hedging activity over the past year.

The collapse in the oil price in late 2014 further fuelled this theory.

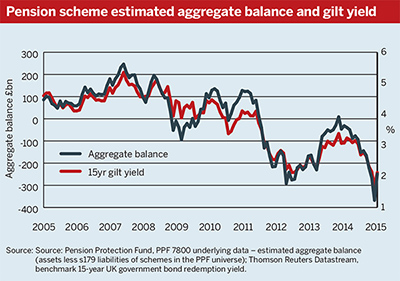

These factors have meant an increased cost of hedging for schemes, with the fall in gilt yields contributing to a record aggregate deficit for UK defined benefit plans of £367.5bn on a section 179 basis at the end of January 2015, according to the Pension Protection Fund (see graph).

We expect gilt yields to rise amid improving economic sentiment and the potential for tighter monetary policy, perhaps through some unconventional channels.

Regulatory pressure on employers over increasing deficits has led many pension schemes to continue purchasing gilts, despite the increasing price of these bonds.

During several rounds of quantitative easing, the Bank of England purchased in aggregate £375bn of gilts – with around £100bn nominal of this in long-dated gilts.

This has impacted the supply of gilts in the market, meaning fewer assets to choose from for pension schemes looking to derisk and ultimately leading to more expensive hedging levels for schemes that have yet to derisk.

Conventional tightening

Key points

-

Pension scheme deficits are close to record levels.

-

There is regulatory pressure on schemes to derisk.

-

Tighter monetary policy is on the horizon.

In the absence of an economic deterioration, the US Federal Reserve is likely to raise interest rates in the summer and we think that the BoE will follow suit without a large time-lag, politics permitting.

Improving statistics in the labour market and stable economic growth should support an increase in the UK bank rate, particularly if we see upward pressure on wages, which could help drive some positive momentum in inflation markets.

With an increasing bank rate, pension schemes should expect higher gilt yields (real and nominal) and more attractive hedging levels in the near-future.

Unconventional tightening

In May 2014, the BoE stated it would not sell gilts on its balance sheet until interest rates are at a level from which they can be cut materially.

The word ‘materially’ has not been defined in this context, but comments from governor Mark Carney in February stated that interest rates could be cut from the current level of 0.5 per cent if deflationary pressures picked up.

With these comments in mind, and a number of European central banks now experimenting with negative interest rates, it is possible we may not be far away from interest rate levels at which the BoE would consider selling some of its gilt holdings.

With many DB pension schemes likely looking for more attractive yield levels to implement liability-hedging programmes, an increase in supply from the BoE might be well received were it to start by selling long-dated gilts.

Kevin Adams is director of fixed income at Henderson Global Investors