Scam reporting structure is not fit for purpose

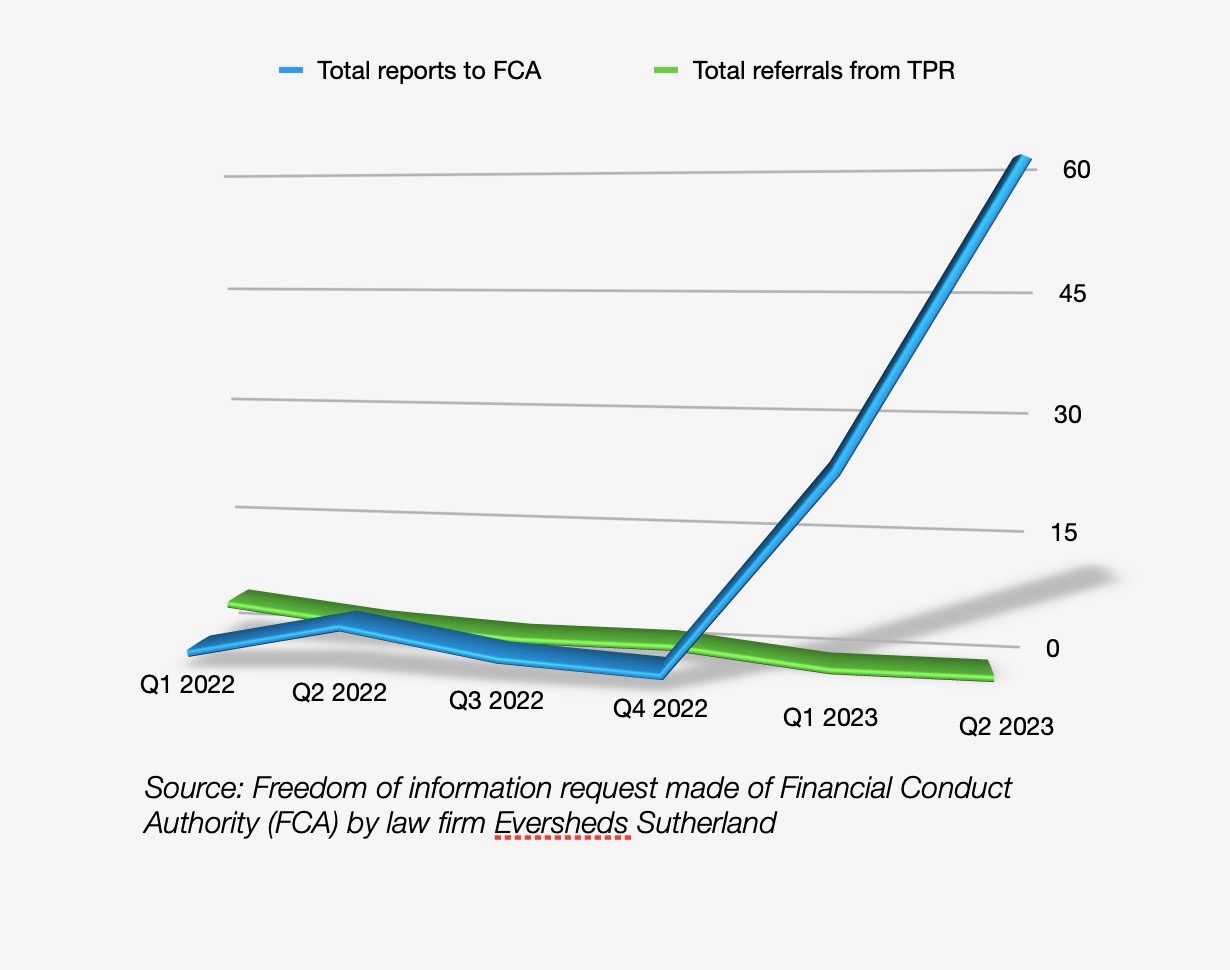

Data from a recent freedom of information request submitted by law firm Eversheds Sutherland showed that reports to the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) about concern with defined benefit (DB) transfers had more than doubled in the second quarter of the year, up to 60 from 24 the previous quarter. Only 13 were reported to the FCA in the whole of 2022.

Charlotte Cartwright, a partner, at Eversheds Sutherland, said that scam prevention can be broken into three key areas – raising general awareness with members about pension scams risk, checking on individual transfers and reporting scam concerns to the FCA.

“To date, there’s been a huge amount done on the first two parts, but this data suggests that there has been less in that third area.

“Without reporting, the FCA cannot fulfil its role of spotting trends and stopping scammers from acting again in the future.”

Realistic expectations

There has been a great deal of denial about reporting levels, Snowdon told Pensions Expert, and there is a danger that small reported numbers may encourage people to believe that pension scams are not a major problem.

There is an expectation that a scam is reported to not only Action Fraud, but the Pensions Regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, and the National Fraud Intelligence Bureau, said Snowdon.

Snowdon has been pushing for some time for there to be a single place to notify the authorities of a scam. PSIG believes this should be Action Fraud, who can then disseminate it to any other agencies.

But the other aspect that makes reporting “impossibly difficult”, is that the system is set up to report a fraud that has resulted in a loss by an actual victim.

“If you represent a pension scheme, you’re not a victim, but you’re trying to help the victim,” said Snowdon.

“And you’re probably not trying to report an actual fraud or scam, but the suspicion of one. But the system isn’t there to record suspicions, and a scheme will struggle to report through that system.”

There is also no feedback from the reporting process, said Snowdon. The reports are absorbed by an intelligence database – like a big vacuum cleaner – in order to help identify trends. But nothing gets done about the individual report.

Victims are discouraged from disclosing scams

More people might be encouraged to report suspicions if the process wasn’t such a “black hole”, said Snowdon, but it is compounded by human nature.

“Many people will not know they have been scammed for a long time. They will then find it hard to believe that the nice person who helped them was the scammer.”

Margaret Snowdon

“Many people will not know they have been scammed for a long time. They will then find it hard to believe that the nice person who helped them was the scammer,” said Snowdon.

They’re ashamed, so don’t want anyone to know, especially not their families, she said, and there is an unfortunate attitude that is prevalent that the victim is somehow at fault for being scammed.

“That has to stop”, added Snowdon. “If you believe the people that are supposed to be helping you believe you are somehow at fault, that just rubs salt in the wound.”

The industry is pulling its weight

Quite apart from the complexity of the reporting process, there is no compulsion for schemes to report, said Snowdon, so why would a stretched scheme invest hours in attempting to report something that may never see the light of day? It’s a perfect storm.

Cartwright at Eversheds is adamant that schemes are doing “a huge amount in this area”, as they are “concerned about protecting their members”.

Cartwright added: “We need to ensure we report concerns about trends to the authorities so they can do their job and stop those scammers from operating in the future.”

Snowdon acknowledges that schemes go to great efforts to support their members, but that the systems designed to prevent scams is not working, as the numbers from the Eversheds FoI request prove.

She is currently writing a paper to encourage the government and industry to take a more holistic look at pension scams and better coordinate the whistleblowing process.

“The first thing to fix is the attitude, then to properly coordinate reporting,” said Snowdon.

“We need to stop the blame game, not just the victim, but the industry for a lack of reporting.

“If you want the industry report, make it a requirement, make it clear what you need to know and make the reporting process transparent.”