Data crunch: The UK private sector defined benefit universe comprises approximately 5,500 schemes with a combined £1.8tn in total assets. The result is a landscape that is uncommonly diverse, although seven key parameters help define scheme characteristics and behaviour.

The first, and arguably most obvious, is size. Larger schemes are more likely to have internal investment teams, demand bespoke solutions from asset managers, and have the clout to negotiate lower fees with service providers.

When looking for best practice, it might make more sense to consider what is achievable based on the experience of schemes with similar characteristics

While the UK is home to some very large schemes, there is a huge tail of small schemes: according to data in the Pension Protection Fund’s Purple Book, 35 per cent of schemes have fewer than 100 members.

Governance standards

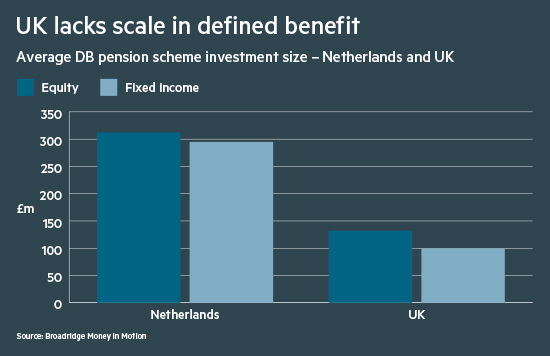

This lack of scale is reflected in Broadridge data on average mandate sizes. The average size of investment allocated to equities and fixed income managers is approximately £130m and £100m, respectively. In both cases, this is less than half the average size of investments made by pension funds in the Netherlands, where assets tend to be far more concentrated among the larger schemes.

Often related to size, governance is also a differentiator. Schemes with strong governance in place have a greater capacity to invest in more sophisticated investment strategies that may be more suited to schemes’ objectives and constraints. The need for better governance standards has driven the shift towards the use of professional trustees and fiduciary managers.

Covenant, solvency and maturity are factors that have an impact on a scheme’s risk appetite. Schemes have a lower-risk threshold if the sponsor lacks the financial strength to pay in additional contributions, if the funding position is already poor, or if the scheme has less time to recoup any investment losses before it starts distributing assets as pension payments.

The scheme’s objective is also salient. Approximately one third of schemes target buyout. These schemes may need to hold more liquid investments and have a shorter time horizon than those targeting self-sufficiency.

A useful framework

The defining feature that is the least tangible, the most idiosyncratic, but is arguably growing fastest in importance is beliefs. This may, for example, influence whether the scheme is more predisposed to use active rather than passive managers. These beliefs may be determined by a scheme’s members, trustees, or external influencers such as consultants.

This final consideration has moved centre stage following new requirements for schemes to consider how environmental, social and governance principles are reflected in their investment strategies.

For example, while one scheme may believe that issues such as climate change are important from a risk-management perspective, others may feel that factors such as corporate governance could lead to outperformance on the basis that better-governed companies could generate bigger profits.

While these seven factors are interrelated and certainly not exhaustive, they provide a useful framework through which schemes can be examined. When looking for best practice, it might make more sense to consider what is achievable based on the experience of schemes with similar characteristics.

Jonathan Libre is a principal in the Emea Insights team at Broadridge Financial Solutions