Crises and volatility have engendered a step change in investment philosophy: to manage the risks before the returns.

While the fundamental principles of investing have not changed, there has been a decisive shift in the attitude among pension schemes towards uncertainty since the financial crisis, which has resulted in a change in the way they manage their investment portfolios.

For the full The Specialist report on investment trends, click here to download the PDF

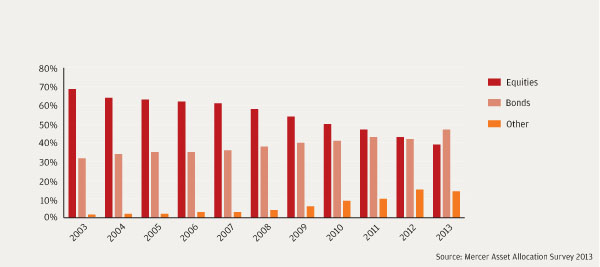

Phil Edwards, principal at Mercer, says: “According to our most recent asset allocation survey, UK defined benefit schemes have reduced their equity allocation to 39 per cent, from 61 per cent in 2007,” (see graph).

Those assets that used to be invested in equities have been roughly split between investments in liability-driven investments, or bonds and alternatives.

Edwards says: “That reduction in equity allocations and the corresponding increase in bonds and alternatives has been driven by the combination of schemes needing to generate a real return to reduce the size of their deficit, but also a strong desire to manage risk.”

Both the Pensions Regulator and sponsoring companies are pushing schemes to reduce risk. The sponsoring company wants to manage the impact of the pension scheme on balance sheets, while the regulator wants to ensure schemes will be able to meet their liabilities.

At a basic level, schemes have two levers at their disposal to reduce the overall uncertainty within the portfolio. Edwards says: “One is to control interest rate and inflation risk through implementing a liability-driven investment approach or increasing the allocation to bonds.

“The other is to reduce equity market volatility while still targeting outperformance above the liabilities by allocating to a variety of other growth assets.”

Investing is about defining and managing the risks first and then maximising returns, rather than the other way round

Pension schemes have diversified their equity portfolios into a wide range of different alternatives. That has included real assets like property, including long-lease property, which provides an income stream that can help to match long-term inflation-sensitive liabilities.

Schemes have also allocated assets to hedge funds, but have moved away from traditional fund of funds towards multi-strategy hedge funds and managed futures. “These strategies provide a different type of exposure to a traditional fund of funds, with the aim of being less correlated with equity markets,” adds Edwards.

In fixed income, schemes have invested heavily in emerging market debt and high yield. Edwards says: “These asset classes are still relatively new for many pension schemes. Their appeal is that they can generate returns above the liabilities but with less than equity market volatility.”

In addition to the shift away from a reliance on equities into a broad range of different growth assets, there has also been a change in attitude in the way schemes manage their investments.

Edwards says: “Schemes are now being more opportunistic and dynamic in the way they manage their investment strategy. Many schemes that do not have the in-house governance budget to manage it themselves have achieved this by allocating assets to a diversified growth fund.”

There has been a similar increase in interest in multi-asset solutions from designers of defined contribution funds. That is due to an increased recognition of one of the most important behavioural finance characteristics: we have a very negative reaction to loss.

While it’s too expensive to provide capital guarantees for DC default funds, designers are using multi-asset funds to mitigate those risks. Although those funds will still invest in equities, they also invest across a number of other asset classes such as property and currency.

As well as using diversification to dampen volatility, some multi-asset funds use additional risk management strategies to keep a lid on equity market volatility.

Mark Humphreys, head of strategic solutions at asset manager Schroders, says: “Our multi-asset funds seek cheaper protection than just buying options to protect from falls in the equity markets. By using futures-based strategies it can mean sacrificing some upside, but it also provides lower cost protection.”

To hedge or not to hedge

While pension schemes have endeavoured to control interest rate risk either by buying more bonds or interest-rate swaps, it has become an increasingly expensive project in recent years as the combination of a low-interest rate environment, quantitative easing and strong demand has pushed bond yields to historically low levels. As a result, many schemes have not been able to afford to increase their interest rate hedges.

But in recent months, there has been a glimmer of hope that the punitively low interest rate environment may be coming to an end. As the economic data on both the US and UK economy has strengthened in recent months, interest rates have started to rise.

Liabilities are long term and are not known with certainty, so it does not make sense to hedge too precisely and with spurious accuracy

Edwards says: “If interest rates were to rise more quickly than the market currently predicts, this would be a godsend for many DB pension schemes because it would cause the value of their liabilities to fall, thus reducing the size of the pension deficit.”

The value of liabilities is highly sensitive to fluctuations in interest rates, particularly in a low interest rate environment. As a rough rule of thumb, an increase in interest rate of one percentage point will cause liabilities to move by 10 to 20 per cent, depending on the maturity of the scheme.

For many sponsoring companies, the recent volatility of pension scheme assets and liabilities has been a step too far and many have put a plan in place to transfer the scheme to an insurance company, ideally through a buyout.

That means any faster than anticipated increases in interest rates will be welcomed as it will cause the cost of interest rate protection to fall, and hedging a higher proportion of the scheme’s interest rate risk will push it further towards the end goal of a buyout.

Twin factors

Rising interest rates are usually accompanied by an increase in inflation; concerns are mounting in the investment community that the period of very low inflation could also be coming to an end.

David Hutchins, head of pension strategies at AllianceBernstein, says: “There is a very real risk that inflation could prove to be far less stable over the medium term. This is the risk that needs to be managed.”

When QE was first introduced there were concerns that the huge quantities of cash would cause inflation to rise rapidly. But that did not happen. Signs of economic recovery in the US and the UK, as well as Europe, have caused those concerns to resurface. A growth in output, along with the increase in liquidity caused by QE, could cause inflation to spike.

The appointment of Mark Carney as the governor of the Bank of England has added to fears of an inflation hike. His new approach to monetary policy with a greater emphasis placed on protecting the economic recovery and less emphasis placed on managing price rises increases this likelihood.

Rising inflation is not good news for pension schemes. DB pensioner payments are linked to inflation increases so rising prices increase the liability burden on a scheme. Humphreys says: “Liabilities for an average scheme have from 70-75 per cent sensitivity to inflation.”

He adds: “We’ve seen a growth in interest in our clients to protect from an increase in inflation over the medium-term through the use of inflation swaps.”

Inflation swaps are more appealing to investors than the more standard index-linked gilts because, as seems likely, if real yields rise over time then the return on the bonds will lag inflation. “Inflation swaps give schemes protection from inflation without exposure to rising real interest rates,” says Humphreys.

But it does not make sense for every scheme to use such precise instruments. Peter Martin, director at JLT Employee Benefits, says: “Liabilities are long term and are not known with certainty, so it does not make sense to hedge too precisely and with spurious accuracy.”

In addition, buying inflation protection is expensive, and is likely to remain so because of the demand from the pension industry, he adds.

The use of real assets

A better long-term solution for inflation protection could come from real assets such as infrastructure, social housing and other property. “These will provide income with some inflation linkage at a much more affordable level,” says Martin.

It’s impossible to find the perfect asset that will always respond the same way no matter what causes inflation to increase. There is no magic bullet

Inflation is not only a concern, however, from a liability perspective – it also has a major impact on the assets of a pension scheme. If a DB scheme wishes to narrow its pension deficit then it must ensure that the returns of its growth assets outstrip inflation.

The challenges inflation poses to the long-term asset value of a portfolio is not confined to DB pensions – it’s arguably an even more serious problem for DC schemes.

Auto-enrolment is dramatically increasing the number of DC members, so designers of default funds have to ensure their investment options will be able to make real returns over multiple decades and in a variety of different inflationary scenarios.

Dealing with inflation over the longer term is not straightforward. There are multiple causes of inflation including oil price shocks, rising demand and currency devaluation. Depending on the cause of inflation, different assets provide different levels of protection.

Just to complicate matters further, there are no guarantees that if a particular event caused inflation to spike in the past that a similar event will cause prices to rise in the future. For example, during the Asian crisis currencies devalued heavily but inflation did not rise.

Humphreys says: “It’s impossible to find the perfect asset that will always respond the same way no matter what causes inflation to increase. There is no magic bullet. The best way is to diversify across multiple assets and give the manager the flexibility to change allocations according to what causes the rise in inflation.”

Managers of DC schemes don’t just have to worry about the impact of inflation on the assets over the long term – they also need to have mechanisms in place to control the impact of both inflation and interest rates as scheme members approach retirement.

Most default schemes try to lock in the capital gains of a portfolio to prevent a sharp fall in the value of asset prices by gradually shifting assets across to government bonds in the five to 10 years before they retire. AllianceBernstein’s Hutchins warns this will provide no protection for pensioners in the run-up to retirement.

He says: “As these bonds nearly always have nominal interest rates this provides no protection against the expectation that long-term inflation will rise.” This is one of the worst times for a scheme member to see the value of their portfolio erode because they cannot reverse the negative performance through contributions.

To ensure these uncertainties are managed correctly, it helps if the manager of the default investment strategy understands the risk tolerance and objectives of the end client.

“As a manager of target date funds, I know that a scheme member has a certain number of years to save for their pension and will then retire. I need to manage their assets against all the risks along that continuum,” says Hutchins.

The new focus on managing uncertainty in the industry has shifted the way pension schemes approach investing and it has changed the mandates that trustees are giving to asset managers. He says: “We’re increasingly seeing outcome-driven mandates with a focus on a risk budget and an end goal.”

That is equally applicable for both DC and DB pensions. For example, a target date fund manager understands the risk capacity of the scheme member is largely based on their age and seeks to achieve the best possible retirement income taking this into account.

For DB pensions, the focus is on the size of the funding shortfall relative to the strength of the sponsor covenant and the manager seeks to maximise returns within this risk constraint.

For the full The Specialist report on investment trends, click here to download the PDF

While uncertainty is still at the heart of investing – after all, returns are a function of risk – pension schemes are much more aware of the impact it can have on their portfolio and that’s fostered a new approach. Hutchins says: “I think investing is about defining and managing the risks first and then maximising returns, rather than the other way round.”

Charlotte Moore is a freelance journalist