Soft drinks manufacturer Britvic is the latest business to attempt to switch the basis for its defined benefit pension increases from the retail price index to the consumer price index, with other companies reputedly queuing up to take legal advice on this very point.

The FTSE 250 company, famous for its Robinsons Lemon Barley Water often featured at Wimbledon, is seeking court approval to impose the change on the members of its defined benefit pension scheme, which has 6,000 former employees and 350 current employee members.

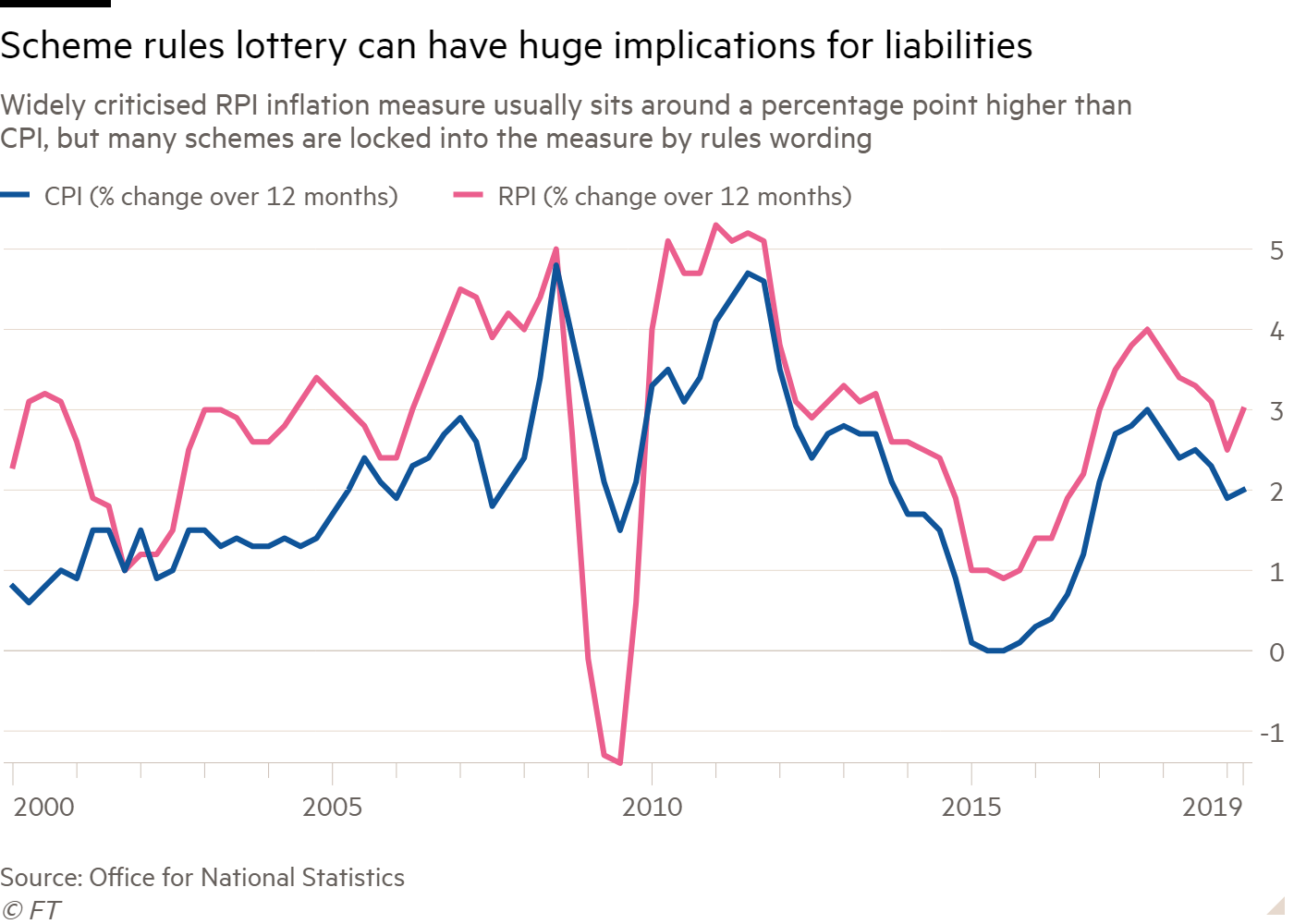

CPI inflation is currently 2.0 per cent, while RPI is 2.9 per cent, according to the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics. Compounded over the years, the choice of the less-generous index can result in pensioners losing thousands of pounds, despite CPI being considered a more accurate index.

According to Britvic’s Annual Report and Accounts at October 1 2018, the group had IAS 19 pension surpluses in Great Britain and Northern Ireland totalling £96.3m, and IAS 19 pension deficits in Ireland and France totalling £9.4m, resulting in a net pension surplus of £86.9m. The DB section of the UK plan was closed to new members on August 1 2002 and closed to future accrual for active members from April 1 2011.

It is a lottery very much dependent on scheme rules and is a very arbitrary way to take things forward

Deborah Cooper, Mercer

A Britvic spokesperson confirmed the move: “We are currently reviewing an aspect of our pension provision. In doing so, we are engaging with all key stakeholders, and have remained in close consultation with the funds’ trustees throughout. As part of this ongoing process, we are now seeking the court’s consent to move this forward.”

Doubts remain as to how successful the soft drink manufacturer will be, however. BT and Barnados have both recently lost court battles on this controversial issue, and Penny Cogher, partner at Irwin Mitchell, says: “Previous cases show that the courts are far from sympathetic to this type of question, no matter how much RPI is shown to be an out-of-date measure for the cost of living.

“While each case does succeed or fail on its own particular merits, the vast majority fail, so it seems unlikely that this company will be able to think of some novel arguments that might encourage the court to change their overall stance on this,” she adds.

Scheme lottery endures

The RPI/CPI debate has been rumbling on ever since 2010, when it was announced that increases to state pensions, public sector pensions and statutory increases for private sector pensions would, in future, be linked to CPI rather than RPI.

Each scheme is different, however, and whether or not it is possible to change the index used turns on the wording of the scheme rules – if increases are in line with statutory rate of increase, then CPI applies. Other scheme rules specifically mention RPI, while others say changes can be made with employers’ consent.

Deborah Cooper, a partner at Mercer, emphasises: “It is a lottery very much dependent on scheme rules and is a very arbitrary way to take things forward.”

Bob Scott, partner, Lane Clark & Peacock, says: “Britvic is the latest of a number of highly publicised court cases (others include BT, Arcadia, Thales, Barnardo’s, British Airways) that have considered whether or not pension schemes can adopt CPI or another index rather than RPI.”

He adds: “There are a number of schemes where the issue is being actively considered by trustees, employers and trade unions, in some cases with legal input from leading pensions QCs.”

The intricacies of scheme rules are not the only hurdle to climb. Even if legal advice confirms that a change from RPI can be made, a suitable replacement index must then be chosen. Mr Scott points to the Thales’ case, where the court ruled that “the index could be changed but only (somewhat perversely) to the RPI, as the wording of their rules required the nearest alternative index to be used]”.

He says: “Even if a change can be made, there is the question of whether it would be an appropriate exercise of power to make the change. It is not clear that ‘saving the employer money’ is a sufficient reason for trustees to agree to such a change.”

Index change can slash millions off liabilities

RPI usually exceeds CPI by around 1 percentage point a year, which in the long run has huge financial implications. Mr Scott says: “For a typical scheme, changing from RPI to CPI might reduce expected future liabilities by around 10 per cent. So, for a company that has a scheme with IAS 19 liabilities of £2bn, that’s a balance sheet improvement of £200m.”

RPI usually exceeds CPI by around 1 percentage point a year, which in the long run has huge financial implications. Mr Scott says: “For a typical scheme, changing from RPI to CPI might reduce expected future liabilities by around 10 per cent. So, for a company that has a scheme with IAS 19 liabilities of £2bn, that’s a balance sheet improvement of £200m.”

Calum Cooper, partner at Hymans Roberson, says it could be even higher: “If all pensions in payment move from RPI to CPI, that would reduce liabilities (ie the value of members’ pensions) by around 15 per cent.”

There are caveats to this rule. Some schemes, notably those belonging to US multi-national employers, are not obliged by their rules to provide inflation-proofing for benefits built up before 1997, when the statutory minimum was introduced.

“For those schemes the impact would be lower, Mr Scott says, adding: “Schemes typically provide indexation up to a ceiling (eg 5 per cent a year or 2.5 per cent a year). The lower this ceiling on future increases the lower the impact of switching to CPI.”

Lawmakers could intervene

There are moves afoot to phase out RPI – Mark Carney has signalled his wish that this happens within a period as short as seven years; and a recent House of Lords report has generated further momentum. If RPI were phased out – or redefined in a similar way to CPI – then the impact of a switch now would be much reduced.

Mr Cooper says: “Where trustees are approached by the sponsor, they will wish to ensure that any alternative CPI interpretation of the rules is in members’ best interests. This may include a consideration of covenant and any additional security they can secure for making the interpretation switch. A higher certainty of receiving CPI benefits in full may more than offset a lower certainty of receiving RPI benefits, for example where the covenant is in a tight spot.”

Given the enduring ‘lottery’ of scheme rules, some have called for government to step in and facilitate a mass transfer to the same basis.

“What is needed is overriding legislation to allow companies to make this change. The only winners are the specialist barristers and lawyers who make thousands of pounds in persuading companies to run these cases,” Ms Cogher says.