The Pensions Infrastructure Platform recently announced its plan to launch a renewables fund separate from its existing offering, but what could this focus on infra's sub-asset classes signal for UK pension funds?

If we take a look across the pensions industry there appears to be a rare consensus on the value of this asset class.

Last month, the London Pensions Fund Authority announced a £500m deal with Greater Manchester Pension Fund to invest in UK infrastructure projects over the next three to four years.

And just last week, we reported the industry-wide Pensions Infrastructure Platform is to add to its existing offering with a separate renewables fund.

The Pip was launched in 2013 with the backing of the National Association of Pension Funds and the Pension Protection Fund, and has so far raised just £350m of a £2bn target.

However, its chief executive Mike Weston says its founding investors are clear on how they want the fund to develop. “The aim is to ensure Pip is at the heart of pension schemes’ investment into infrastructure,” he says.

In an asset class where it has been said there are too few investable options for UK pension schemes, it might be easy to assume that infrastructure deals among schemes outside of the platform – such as the LPFA and GMPF tie-in – could create competition, either for assets available or indeed for potential Pip investors.

Risk and renewables

There has been a greater demand for the sub-asset classes within the infrastructure bracket such as renewable energy projects and social infrastructure.

However, investments in some of these areas are not as straightforward and investors should be wary of the extra risks involved.

While the demand may be just as great for fossil fuel investment, the need for direct institutional investment might be less given the dominant role played by utilities and big industrial sponsors in this market. This means there are subsequently fewer investable opportunities.

But social and political reform programmes are also stimulating the renewable markets.

In credit rating terms, the majority of social infrastructure investments would be considered investment grade, while renewables would often be slightly below this in sub-investment-grade territory.

In addition to renewables, there is also an increasing interest in social infrastructure, although at this stage there are not as many opportunities as in other areas.

Renewables and social investments will continue to be important, especially in the UK. There is also big potential in the energy-efficiency market, as it should be easier and cheaper to improve upon existing infrastructure to create more efficient energy use than to build a whole new infrastructure base.

David Cooper is executive director of debt investments at IFM Investors

But far from competing for target assets, Weston says the local authority schemes’ deal demonstrates the asset class’s huge financing needs, and their move is a validation of the Pip concept of schemes collaborating to access infrastructure.

That need, according to S&P, is estimated to be around the $3tn (£2tn) mark globally. However, in Europe, there are concerns that regulation around capital requirements – such as the Solvency II directive – is holding back many institutional investors from less liquid asset classes.

Around £100bn of investment is estimated to be required in electricity generation and networks by 2020

Government's National Infrastructure Plan

However, Mark Latimour, partner at law firm Eversheds, thinks this might be being overplayed. He says it is rare for most pension funds to invest in illiquid assets directly, choosing instead to go via the pooled fund route.

“It would be more accurate to say their investment decisions are coloured by the need for more liquid assets,” he says.

At the mercy of energy policy?

Investing in sub-sets of infrastructure is nothing new, but the fact that the Pip is eyeing renewables in particular is telling.

The government’s National Infrastructure Plan, published in December 2014, spelt out how the global need translates for UK energy. The report said: “Around £100bn of investment is estimated to be required in electricity generation and networks by 2020.”

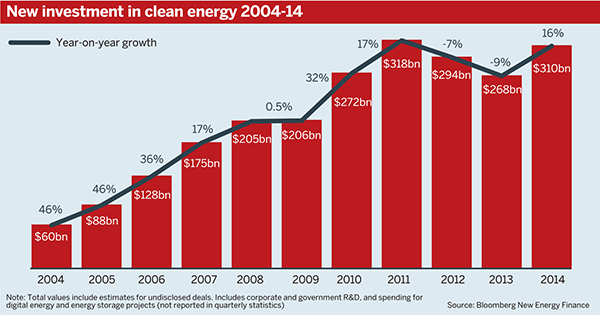

According to a report released last week by Aquila Capital entitled ‘Real Assets – The New Mainstream’, of the total investment made in generating capacity across the globe, renewables account for more than 60 per cent.

“It is estimated that renewable energy generation will triple between 2010 and 2035, by which time it will account for almost a third (31 per cent) of the global energy mix,” it said.

This, coupled with the longer-term shift away from fossil fuels, means energy sourced from wind, water and sun is becoming increasingly compelling.

Toby Buscombe, global head of infrastructure at consultancy Mercer, says renewables are heavily dependent on technology and the regulatory regimes that “wrap around” such projects, but their risk-return profiles can form a useful part of a wider infrastructure portfolio for the larger schemes able to take advantage. He adds a particular concern for the UK and Europe is the “continuing evolution in energy policy”.

The Aquila report takes a more balanced view of this risk, saying the rigour applied around such regulatory requirements makes it easier to prepare yield forecasts, for example.

However it also says investors should be mindful of renewables’ dependence on a favourable regulatory environment.

Both Buscombe and the Aquila report point to the ability of renewables to provide inflation protection. Aquila says: “Renewable energy investments offer a degree of inflation protection, as the price of electricity – provides it is sold via the market – factors in inflation.”

But the report warns the true risk-return profile of such projects depends heavily on where in the value chain the investor gets involved.

Nevertheless the political incentives and growing global demand for energy – along with the falling cost of technology and improved weather data – is gradually driving up interest in the sub-asset class.

For long-term investments ranging from 10-25 years, for example, Aquila expects UK investors to make around an 8 per cent return from solar and 6-9 per cent from wind. But wider market acceptance of the long-term strengths of such industries will be key to the sector’s growth among UK pension fund investors.

Perhaps the Pip’s show of commitment will get the herd moving.