Tracking the rise and uncertainty of responsible investment

Socially responsible investment is undoubtedly gaining popularity among both asset managers and trustees.

But its continued growth depends on the outcome of a fiduciary duty review by the Law Commission, which may lead schemes to ignore the sustainability of investments in favour of their risk-return profiles.

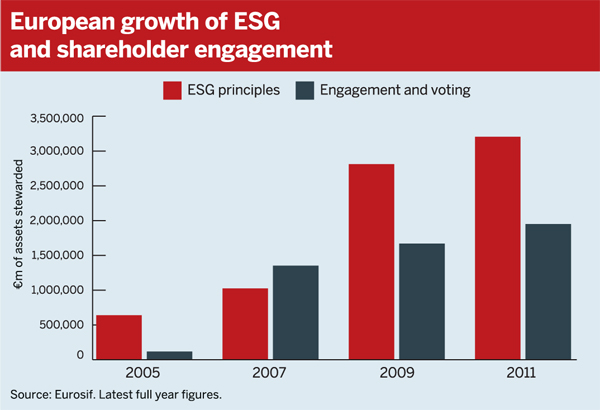

Increasing demand for responsible investment is driven by a combination of engagement and environmental, social and governance concerns, as well as from asset managers looking towards long-term asset growth.

A 2012 study by sustainable investment think-tank Eurosif showed that shareholder votes were being applied to more than £825bn of assets in the UK, while ESG principles were woven into £580bn of investments.

“What we’ve seen over the past decade is that growth in SRI has outpaced growth in many other areas of asset management,” says Ominder Dhillon, head of distribution at Impax Asset Management.

Eurosif data show growth rates between 10 per cent and 54 per cent for different sustainable assets, Dhillon adds.

Managers present the wide range of responsible investing approaches as being something that can fit into different parts of a scheme’s portfolio.

It is often seen as a tool to manage risk, but is also being promoted for growth opportunities in areas such as alternative energy.

Dhillon says responsible investment can play a key role in specific parts of the investment strategy, specifically around long-term risks and alternative sources of income.

“That’s where we think SRI really comes to the fore because longer-term risks and opportunities are by their nature harder to model, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t important,” he adds.

How it's done

Responsible investing for growth often means investing in a build-and-sell model to generate return.

Scheme guide

Eurosif has defined several ways schemes can responsibly invest:

- Sustainability-themed investment: Investment in themes or assets linked to the development of sustainability. Thematic funds focus on specific or multiple issues related to ESG;

- Integration of ESG factors in financial analysis: The explicit inclusion by asset managers of ESG risks and opportunities into traditional financial analysis and investment decisions based on a systematic process and appropriate research sources.

- Impact investment: Investments made into companies, organisations and funds with the intention of generating social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. Impact investments can be made in both emerging and developed markets, and target a range of returns from below market-to-market rate, depending upon the circumstances.

This is intended to create benefits for society through the construction of infrastructure projects and returns for the investor through the sale. But this also introduces construction risk to the portfolio.

Another approach is buying an operating asset, which provides income for the investor while they own it.

“Because it’s almost like a bond it may be used for matching,” says Dhillon. “But it can just as easily be used as a growth asset.”

Implementing SRI strategies may be more challenging for smaller schemes, as building projects and operating assets can require a large pool of resources. However, bodies such as the National Association of Pension Funds provide collaborative opportunities to get over this hurdle.

“The smaller you are, the more you can benefit from collaboration,” says Aled Jones, head of responsible investment for Europe at consultancy Mercer.

However, some experts are wary of schemes becoming too focused on responsible investment as it may affect their judgment of what investments are best for their members.

“[SRI] is one of many considerations that schemes should take into account but it’s not the be-all and end-all,” says Jane Samsworth, head of pensions at law firm Hogan Lovells. “Schemes should resist pressure to invest in anything other than the best interest of the member.”

Under review

The debate over what is in the best interest of the member is ongoing, with the Law Commission’s consultation closing last week on its review of the fiduciary duty for investment intermediaries. Some in the industry believe the commission is against recommending a codified fiduciary duty.

Such a duty would lead to less flexibility in the way it is interpreted, says Samsworth.

“Trust law has been able to adapt to changing conditions over the years,” she says. “That’s the most important thing.”

Law surrounding fiduciary duty is based on the well-known Scargill case, which ruled investments should be judged almost entirely based on financial criteria rather than moral or political views.

“Cowan v Scargill is still good law and helps trustees to stick to the knitting and resist outside pressure to invest in any particular way,” says Samsworth.

But others believe that the potential consequences of investing in companies that are unsustainable makes ESG factors an increasingly critical part of fiduciary duty.

Case law states that trustees consider circumstances that they knew or ought to have known are relevant at the time they act.

Raj Singh, programme director at sustainable investment trade body UKSIF, emphasises the importance of what trustees ought to have known. “We can’t see how a trustee cannot consider, for example, climate change on this basis,” he adds.

The Law Commission closed the consultation for the review last week. A report with recommendations is expected in June 2014.

Regardless of the outcome of the review, some asset managers are optimistic about the future of responsible investment. On the scheme side, Jones predicts its popularity will continue to grow, becoming a standard consideration for schemes in the next five to 10 years.

Managers are especially optimistic about the potential for growth in a number of areas such as pollution management, water infrastructure and energy efficiency.

“We’re seeing as much investment planned for 2014 as we had for 2013,” says Peter Rossbach, head of private equity and infrastructure at Impax.

Most Viewed

- What does Labour have in store for the pensions industry?

- LGPS latest: GLIL backers invest £475m for UK infrastructure push

- Dashboard costs rose by 23% in 2023, figures show

- Border to Coast launches UK strategy in major private markets push

- How the pensions industry can better support people with mental health problems