Looking for a silver lining: Focus shifts to housing wealth as pension incomes hit a high

Analysis: Statistics seem to show that pensioners' incomes are now higher than other people's, but experts say there are many facets to the intergenerational fairness question.

About 18 months ago, the Institute for Fiscal Studies published a report that quietly acknowledged what appears to be a shift in wealth and living standards between generations in the UK.

Fifty years ago, being old was a pretty good indication of poverty; pensioners are now less likely to be poor

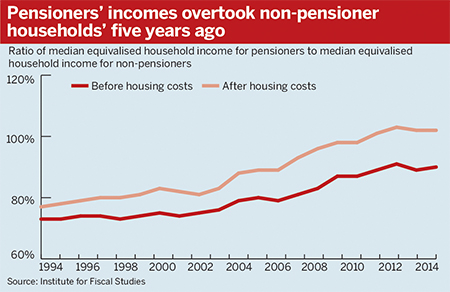

It said that, taking into account household size, a median pensioner’s income reached 89 per cent of a median non-pensioner’s in 2013-14, while after housing costs, “the median pensioner now has a higher equivalised household income than the median non-pensioner”, the report, ‘Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2015’, noted.

In the 2016 version of the same report, the IFS notes: "The income of the median pensioner rose from 81 per cent of the income of the median non-pensioner in 2007–08 to 89 per cent in 2011–12 (and went from 93 per cent to 101 per cent on an afterhousing-costs basis which, when comparing age groups, is arguably more relevant)."

Andrew Hood, senior research economist at the IFS, says this is the first time since 1961 that pensioner incomes have overtaken those of non-pensioners.

Better state provision – mainly through pension credit, fuel payments and the like – coupled with larger private pensions have lifted pensioner income levels, he says.

“On top of that what you’ve had since 2007-08 is that we’ve seen big falls in real earnings, and that has reduced the income of working-age households.”

So while “50 years ago, being old was a pretty good indication of poverty… pensioners are now less likely to be poor”.

While this is a positive development for those heading for retirement, it is unclear how long the trend might continue.

The IFS has not made projections, but Hood says a lot will depend on how fast earnings grow relative to prices as the triple lock means state pension income will grow in line with earnings.

As for private pensions, a slow-down is expected at some point, though when can’t be said for sure: “In the past 30-40 years, each cohort had more private pension income [than the one before it]. What we don’t know is whether that is slowing down or not yet.”

Western economies show similar trend

The UK is not the only country where pensioner incomes have improved to the extent that many pensioners are now better off than the average non-pensioner.

Countries like France and Luxembourg have seen median pensioner incomes surpass those of younger people for a number of years; Eurostat shows the median equivalised income of over-60s in France at €22,222, compared with €21,833 for the 18-64 age group.

Pensioners are very up for spending time and energy for lobbying and their own interests

“Based on the earnings developments of the past few years, when earnings reduce, pensions should be lowered or at least not increased,” says Michela Coppola, senior economist at Allianz Asset Management.

However, “for political reasons pensions have been frozen,” she adds, referring to the fact that older people are significantly more likely to vote and therefore governments tend to give them preferential treatment.

Older people are more in need of protection

But although these figures look stark, some point out that pensioners cannot easily increase their income, making them more dependent on state protection.

And they will naturally have had more time to accumulate wealth and increase their income levels, says Ros Altmann, former pensions minister.

“If you have reached the end of your working life you would expect to have more assets and have reached peak income. After that it will either decline or stay level but it won’t increase,” she says.

Altmann also notes that the term ‘pensioner’ refers to a heterogeneous group of people who can be decades apart in age. While many baby boomers might be doing well, “people currently in their mid-70s, 80s and 90s are generally very poor,” she says.

She adds that statistics can be “muddied” if they include people who work past retirement but draw a state pension and will therefore still be counted as pensioners.

Be careful what you wish for

Hugh Nolan, president of the Society of Pension Professionals and director at consultancy Spence & Partners, says the IFS figures “are quite shocking”.

He agrees with Coppola that politicians strongly protect pensioners for reasons not strictly related to economics.

“It’s not surprising that political focus is mainly on those who go out to the ballot box,” he says.

But Nolan warns that although the strain of paying for older generations’ benefits might become intolerable for younger people in the future, they would be shooting themselves in the foot by going down extreme routes.

“It might swing the other way [and people might say], ‘We’ll stop all state pensions because we’re sick of them’, and that would be wrong because of future generations.”

Pensioners 'are very up for lobbying'

For Angus Hanton, co-founder of the Intergenerational Foundation, the pendulum has swung too far in favour of older generations; he says pensioner benefits should be means-tested.

No details on homes for older people

In its recent white paper on the housing market, the government says the secretary of state will produce guidance for local planning authorities on how their local development documents should meet the housing needs of older and disabled people.

“Helping older people to move at the right time and in the right way could also help their quality of life at the same time as freeing up more homes for other buyers,” the white paper says, although it cites numerous barriers to doing so.

The government is not presenting a solution but says it is committed to “exploring these issues further” with housebuilders, mortgage lenders, clinical commissioning groups, housing associations, local authorities and “older people and the groups that represent them”.

“We calculate that there are over 2m older people in households with a million or more of assets including housing and pension wealth,” Hanton says.

“Some of the benefits older people get are universal benefits… those are all tax free.”

He says today’s retirees are in better health and can expect to live longer than previous generations, meaning they have time and energy to spare: “They’re very up for spending time and energy for lobbying and their own interests.”

He says people should be voting from age 16 so the young have more say in decisions that affect them.

Housing plays an important role

Hanton also stresses the importance of housing wealth, and says even though an older person living in a highly valued house might not have much income, this constitutes a choice on their side.

“Our premise is that they are still well off even if they haven’t converted that wealth to income,” he says.

“They have to face that choice. The obvious thing that they can do is downsize; [or] they can take a lodger, that would help intergenerational understanding.”

But downsizing might not always be an option, according to Altmann.

Intergenerational fairness debate heats up as inquiry is launched

An inquiry into intergenerational fairness, aiming to bring more clarity to the often heated debate about who gets what from the state and employers, has been welcomed by experts.

“There is not enough appropriate housing for older people; at the top end yes, but for the average person, they’re not going to buy a first-time buyers’ flat.”

Altmann says if older people had somewhere they could downsize to it would “solve some of the logjam in the housing market” and “will ultimately save costs in supporting older people”.