EMD report: how to take advantage of the dip

While emerging market assets have been battered in recent weeks, the debt sell-off could in fact provide added opportunity for pension schemes.

The recent emerging market debt sell-off may have spooked some investors, but others argue this may be the time for pension schemes to increase allocations to the asset class.

Even though EM assets have taken a battering in the past month, the strategy’s defendants insist this is a technical correction rather than a problem endemic in these markets.

Eighty-eight per cent of emerging market fixed income is not captured by an index

“Current prices do not reflect underlying risks in the markets,” asserts Jan Dehn, head of research at Ashmore Investment Management.

Prices in these markets tend to move for reasons not associated with underlying fundamentals, such as the US Federal Reserve’s announcement on the potential reduction of quantitative easing from late May, Dehn adds.

Japan’s announcement of further QE as part of its ‘Abenomics’ economic policy – named after the country’s prime minister Shinzo Abe – has also increased bond volatility substantially.

This has opened a window for long-term investors such as pension schemes, say EM proponents. “There is a huge opportunity for emerging markets to outperform after the correction,” Dehn says.

Rob Stewart, managing director of emerging market debt at JPMorgan Asset Management, agrees. “The outflows from retail and crossover investors are being matched by inflows [from] institutional investors taking advantage of depressed valuations.”

Corporate bonds

Like with developed world fixed income, schemes are being advised to look across the emerging market credit spectrum in the hunt for yield.

Daniel James, head of global markets at Aviva Investors, argues corporate debt is the “weapon of choice” for investors currently allocating to emerging market debt. There has been a fervour of activity in the corporate bond market with year-to-date gross issuance of $158bn (£101bn).

He says: “With companies often rated better than their underlying sovereigns, together with their shorter duration structure, this is appealing to investors as they become more conscious and concerned about the future of US Treasury yields.”

Helene Williamson, head of emerging markets debt at First State Investment, says investors need to be more selective in 2013 and look for more credit differentiation.

“We currently see most value in good-quality export-oriented EM corporates in the investment-grade sector and in higher-quality sovereigns,” she says.

However, Richard Carlyle, managing director at asset manager Capital International, does not agree, and has pulled back on exposure to corporate bonds.

There are signs that the emerging corporate bond market is becoming overheated as the number of lower-quality companies jumping into the corporate bond fray increases to fill investor demand, he says.

“There are a number of asset managers now offering dedicated EM corporate bond funds, which is also a worry,” he adds.

Government debt

The underlying case for EM government bonds has not changed. Strong economic fundamentals including low levels of government debt and strong consumer consumption, compared with developed markets, are key drivers.

James says: “Local and hard currency emerging market debt is currently returning 5.6 per cent and 5 per cent respectively, which in a market where investors have to dig deeper to find yield is very attractive.”

It is lack of knowledge and research that is prompting huge outflows in the region, say EM defenders.

Dehn says the view that lumps together emerging markets is “primitive” – a bond from Mexico should not be treated the same as one from Rwanda.

The manager also criticises the “financial apartheid” where emerging markets are considered risky and developed markets are not.

“Emerging markets are safer than developed markets,” he contends, arguing developed economies are riddled with debt and developed market bonds have garnered huge losses.

The use of emerging markets by pension schemes has been criticised by consultants as below par, as the less liquid, less accessible parts of the markets are being ignored.

“Eighty-eight per cent of emerging market fixed income is not captured by an index,” says Dehn.

He concludes schemes are therefore cutting themselves off from huge swaths of the credit spectrum if an index is followed.

Which countries offer best value?

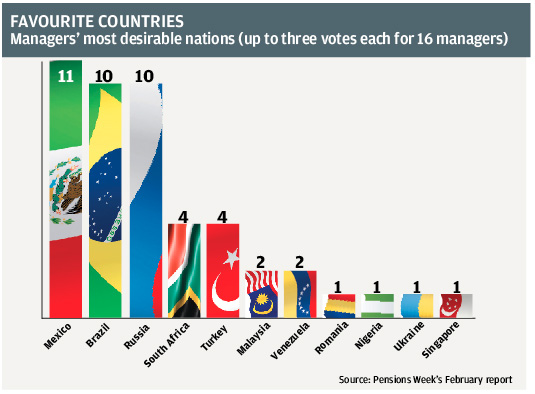

Earlier this year, a Pensions Week survey of EMD managers found Mexico was looked upon most favourably (PW 05/03/13). This was followed closely by Brazil, Russia, and South Africa.

Mexico is considered attractive due to its strong fundamentals. Steve Saruwatari, EM product specialist at Western Asset, said at the time: “Labour costs relative to China have improved in Mexico’s favour and the proximity to the US allows [it] to enjoy strong support from US imports.”

The stability of the government, including labour reforms and an overhaul of the oil industry, have been good for the economy. “There is a strong consensus about Mexico,” says JPMorgan’s Stewart, adding that as investors pile into the country, there is a worry a bubble could form.

Capital’s Carlyle says Brazilian inflation-linked bonds are also attractive. Stewart cited the recent scrapping of the country’s IOF tax, a 6 per cent levy on fixed income, earlier this month as a reason why the country was “interesting”.

Most Viewed

- What does Labour have in store for the pensions industry?

- Dashboard costs rose by 23% in 2023, figures show

- LGPS latest: GLIL backers invest £475m for UK infrastructure push

- Border to Coast launches UK strategy in major private markets push

- How the pensions industry can better support people with mental health problems