Delayed gratification and the spirit of the 60s

Editorial: The marshmallow test is one of the best demonstrations of humans struggling to opt for delayed reward over instant gratification.

Children are asked to sit with a marshmallow in front of them for 15 minutes and told that if they succeed in not eating it, they will receive two marshmallows instead of one. Their faces express all the agony involved in resisting the urge to gobble the sweet down.

Saving is similar in many ways. Our article on financial education takes a closer look at delayed gratification, and what can be done to make people put something away now to have more tomorrow.

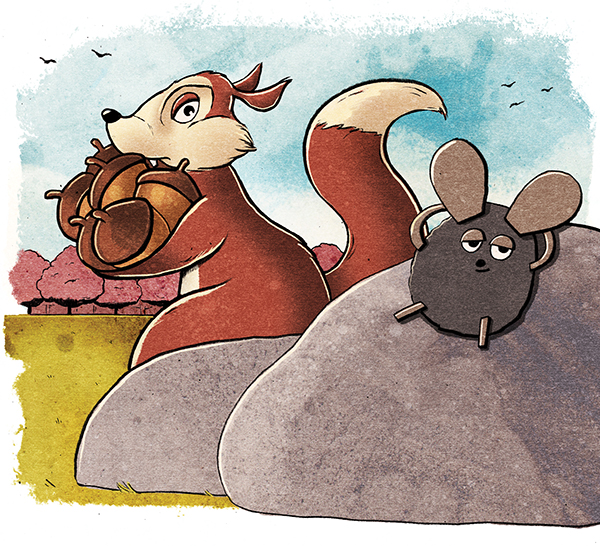

The spirit of deferring consumption has also been applauded by consultancy Redington’s co-founder Robert Gardner, who is on a mission to teach the next generation about saving with his children’s book Save your acorns, featuring two little squirrels.

In the book, reckless monkeys waste their bananas but are luckily helped out by the bears, who thought ahead: they had collected and stored lots of berries.

Illustration by Ben Jennings

What struck me is the difference in attitude between this children’s book and the ones I grew up with, many of which were positively anti-saving, and instead celebrated the importance of imagination, music and philosophy as counterbalances to materialism.

A well-known children’s book from 1967, Leo Lionni’s Frederick, tells the story of a seemingly lazy mouse, who sits back while others collect food for the winter. However, when the food eventually runs out in winter, it is Frederick who ‘feeds’ the other mice with the thoughts and stories he ‘collected’ earlier.

German children’s book author Janosch in 1979 created a little book about a cricket who does nothing but play the violin all summer long as the other animals prepare for winter. When the cold sets in, only the mole gives her shelter, but her music has a value in itself, bringing him happiness.

How times have changed. These books must have been written in the heyday of defined benefit pensions and the social state, when there was no anxiety about how tomorrow’s elderly would be able to fund themselves.

As DB pensions are in decline and uncertainty is becoming the new norm, it is perhaps right that we teach our children to prepare for the future as best as they can financially.

But there could also be a lesson from the 1960s in all this – the value of teaching future generations that the status quo doesn't always have to be accepted and dreaming is sometimes necessary.