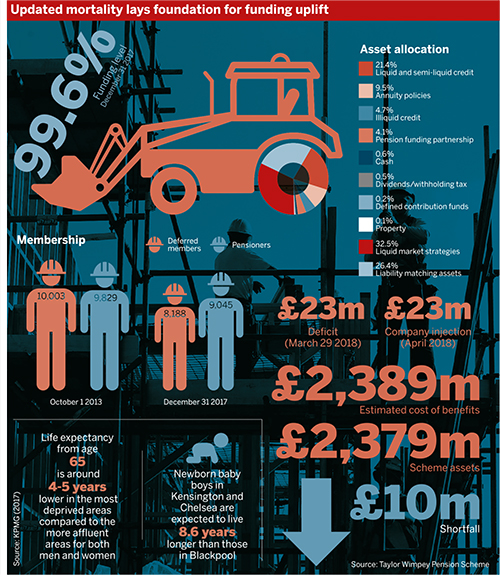

Trustees of housebuilder Taylor Wimpey’s pension plan, which completed a medically underwritten mortality study last year, have announced that the scheme has reached full funding following a £23m injection from the company in April.

The scheme’s improved funding position comes as funding levels are rising across the FTSE 100.

Last month, consultancy LCP released figures indicating that blue chip schemes have reflected a year-end accounting surplus for the first time since the 2007/08 crisis.

However, while some schemes may have a surplus on an IAS 19 accounting basis, that does not necessarily mean that there will also be a surplus on a scheme funding basis.

For a large scheme, the individual information is likely to average out so you wouldn’t expect it to be very different from a postcode approach

Charlie Finch, LCP

The £2.38bn Taylor Wimpey Pension Scheme reported an actuarial deficit of £222m at the end of December 2016, representing a funding level of 91 per cent, according to the scheme’s May 2018 newsletter.

The pension scheme’s actuarial valuation process was extended to include a Mums, undertaken with medical underwriter MorganAsh in the summer of 2017.

Contributions on hold

The scheme received an update on its financial position at March 29 2018 from its actuary, which indicated a £23m deficit. As a result, the company took the decision to make a top-up payment to the fund of £23m in April 2018, resulting in a fully funded scheme at that time.

Prior to this notice, the scheme had agreed a more generous contribution plan with its sponsor in the aftermath of its actuarial valuation.

The newsletter shows that until March 2018, the company had agreed to pay annual contributions of £16m. From April 1 2018, the company was to provide £40m a year in contributions, along with a yearly contribution of £2m towards the costs of running the scheme, until January 1 2021.

This plan was subject to the scheme remaining in deficit. Since the subsequent update, these contributions have been put on hold unless and until its deficit falls below 96 per cent.

The scheme could not be reached for comment on its funding position. The company declined to comment.

Employer covenant was recently cited as the second highest risk facing DB schemes in the eyes of trustees, according to audit, tax and advisory firm Crowe Clark Whitehill.

In general, said Richard Farr, managing director at covenant specialists Lincoln Pensions, employers will regularly ask schemes to “push the bar” on assumed investment returns before offering more backing.

Should the schemes fail to meet these assumptions, the sponsor will then supply cash, he said.

Farr summarised the attitude of most sponsoring companies as a will to see their schemes “get bigger first” before they increase their backing.

He observed that sponsors want to “make that short-term marginal pound investment work for the company first, to build the covenant up, and then derisk”.

Mums are more suitable for smaller schemes

Following the scheme’s valuation, the trustees had envisaged a “short recovery period of only four years”, according to the newsletter, which included the now-scrapped contribution plan.

A Mums was commissioned along with the use of postcode analysis data, the latter of which has historically formed the basis of member life expectancy.

Members’ postcodes can be used to organise a scheme’s membership into groups prone to have similar characteristics, such as occupation and socio-economic status, and lifestyle habits, including smoking and obesity.

For the Mums, MorganAsh took data on each respondent from the scheme membership, underwrote each case to produce a life expectancy of each individual and aggregated their findings. This produced an estimate for the scheme.

The study surveyed 3,206 members covering 45 per cent of scheme liabilities, between the ages of 55 and 80. It had a 60 per cent response rate from members, equivalent to £629m of the scheme’s liabilities at December 31 2017, according to Taylor Wimpey’s 2017 annual report.

According to the newsletter, the exercise showed that members may not live as long as the actuary had predicted, meaning the cost of providing benefits was lower than previously thought.

The liability reduction resulting from this study and other longevity data sources, which came to around £90m, “has been partially offset by a 0.15 per cent decrease in the discount rate with the balance of actuarial assumptions staying broadly stable”, the annual report read.

It is not the first time the scheme has made use of medical underwriting. In 2014, it conducted a medically-underwritten bulk annuity transaction.

Using this bulk annuity transaction, it sought to derisk the liabilities of its most burdensome 99 pensioners and their contingent spouses, according to MorganAsh.

Andrew Gething, managing director at MorganAsh, disclosed that Taylor Wimpey’s Mums was the largest such exercise completed by the company, by number of scheme members sampled. Using an online medical survey, the company was able to extract information from those who are abroad, “who you wouldn’t get into a postcode model”, he said.

He suggested that certain sectors may have a preference towards using Mums. “We have seen some sector bias. We did a lot of publishing companies the last couple of years, and certainly we’ve done a few building firms now,” he said.

Gething observed that Mums are commonly driven by “reasons to question the existing valuation”.

This may be down to differences between real-world data and the “theory being produced by the actuarial valuation”, he added.

“We have seen some sector bias. We did a lot of publishing companies the last couple of years, and certainly we’ve done a few building firms now,” he said.

But Charlie Finch, partner at consultancy LCP, queried the Mums resulting in the reduction of the scheme’s assumed life expectancy with a corresponding fall in liabilities.

“There’s no reason necessarily why it should result in a reduction, as you’d expect on average some schemes to have more people in poorer health and some schemes to have fewer people in poorer health,” he said.

Mums are more suitable for smaller schemes, he said. “For a large scheme, the individual information is likely to average out so you wouldn’t expect it to be very different from a postcode approach.”

A pitfall of the postcode model is “that it’s correct on average, but it may be too high or too low for your particular scheme if you’ve only got a small number of members,” he added.

Taylor Wimpey scheme spreads its bets

The scheme has successfully balanced a return to full funding with a drive towards derisking its investment portfolio.

This effort has continued for a number of years now, and the scheme has recently updated its investment strategy in tandem with its consultant Redington. Changes included splitting its diversified risk premia allocation between two asset managers at the beginning of 2018.

“Following the conclusion of the scheme’s actuarial valuation, we will be working with Redington to review the investment strategy with a view to derisking the portfolio where possible,” the scheme’s newsletter read.

This decision to spread the investment was taken “with the aim of reducing the risk of a manager underperforming”, it added.

It also removed risk from its volatility-controlled equities holding by shifting back to its target strategic asset allocation following “very strong positive performance in 2017”. The allocation delivered returns of 30.6 per cent.

Taylor Wimpey had previously overhauled its physical equity investments into a synthetic portfolio in 2016 as part of its drive to reduce its investment risk.

The newsletter showed that the scheme has also made a new investment into KKR’s opportunistic illiquid credit fund and topped up its allocation to a Blackstone-run fund of hedge funds “by a small amount to achieve a better management fee for the scheme”.

Deon Dreyer, managing director at technology provider Ortec Finance, said that “10 years ago, because of the number of providers, you didn’t really have the option” of dividing a risk premia allocation across managers.

The increased size of the market has since spawned the range of options available to schemes, Dreyer said, adding that “very often they are complementary”.

Balancing protection with business growth

Charles Cowling, director at JLT Employee Benefits, said that underlying market conditions have assisted the recovery in FTSE 100 scheme funding levels.

“Equity markets have continued to do well,” he said. “Interest rates and inflation are not doing anything difficult for pension schemes, which is important because what we’ve seen over a number of years is the impact of interest and inflation significantly hitting liabilities.”

Last month, the Pensions Regulator, which monitors employer actions in the UK in relation to their schemes, laid out its new “clearer, quicker and tougher” stance in its corporate plan.

How can schemes assess employer covenant strength?

Angus Peters, associate editor at Pensions Expert, examines the ways schemes can monitor employer covenant strength.

Cowling predicted that the regulator following through with a tougher approach in demanding money from sponsors could run into trouble with politicians seeking to maintain “being kindly disposed towards businesses”.

He observed the government’s “really tough political balancing act” between satisfying the needs of businesses in order to encourage stable markets, while emboldening the regulator with greater powers as laid out in the recent white paper.

“We wait to see not only what powers that might be, but how the regulator is going to use those powers,” he said.