Infrastructure opportunity too good to ignore

From the blog: Infrastructure debt is gaining recognition as an asset class that can offer pension schemes stable income-oriented returns over long-term horizons, but accessing this opportunity isn’t always straightforward.

Around the world, ageing infrastructures are starting to crumble. This is all too evident in the UK.

Nearly 45 per cent of London’s water mains are more than a century old. No full-length airport runways have been built in the southeast since the second world war. And drivers claimed more than £3m compensation for damage inflicted by potholes on UK roads last year.

Governments are spending less on public investment projects, while regulatory constraints have forced banks to cut back infrastructure lending. The end-result is a massive funding shortfall.

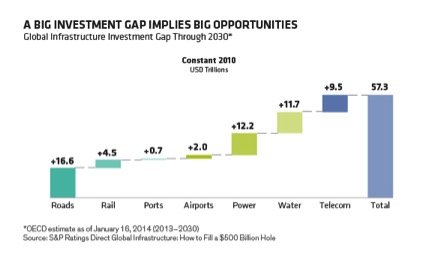

It’s estimated there’s an annual gap of about $500bn (£328.8bn) between investment needs and available public funds globally through to 2030.

Institutional investors, including pension schemes, are keen to step into this opportunity.

Digging deeper

Infrastructure assets span hospitals and schools, water, gas and electricity facilities, airports, roads and rail, as well as telecom towers and motorway service stations.

In some way, they all provide essential services and, therefore, deliver steady and visible cash flows over economic cycles.

Investing in these long-dated real assets can help pension schemes meet their long-term liabilities. But picking the right assets, and avoiding the temptation to go off piste, are crucial to long-term success.

Regulated utilities, like water and energy, can be particularly attractive, as can certain transportation and renewable businesses. Regulatory oversight often provides extra certainty about future revenue streams.

Many UK investors prefer local investment due to the UK’s track record of privatising assets. However, continental Europe also offers a rich seam of investable assets, underpinned by a stable and supportive political and regulatory backdrop.

There are plenty of opportunities in both new greenfield projects and more established brownfield assets. Because the latter are operational and already generating income, they’re less vulnerable to the extra costs and delays that can sometimes hit greenfield projects that run into trouble.

Analysis suggests some €100bn (£70.5bn) in infrastructure debt is likely to require refinancing across Europe over the next 10 years or so, providing a vast opportunity not to be ignored.

Gerry Jennings is head of global infrastructure debt at AllianceBernstein

Most Viewed

- ‘A fundamental point of fairness’: MPs call for action on discretionary increases

- TPR to scrutinise ‘systemically important’ professional trustee firms

- What does Labour have in store for the pensions industry?

- Defining the role of the scheme actuary

- Five themes at the forefront of a sustainable future