Does your derisking strategy add risk?

From the blog: There is an analogy I like to draw involving something everybody knows: yoghurt. People have been happily consuming yoghurt for hundreds of years, but half a century ago people started to worry that too much fat was bad for their health.

Food producers responded by offering low-fat yoghurt.

Did ‘low-fat’ mean ‘less health risk’? Well, possibly not. Removing the fat had an undesirable consequence: a loss of flavour. Manufacturers solved this by replacing fat with sugar, the dietary demon of the present.

So the low-fat yoghurt had a lot more sugar, which was arguably just as bad for you – and maybe even worse.

Similarly, if you’re a pension scheme, changing your investment strategy in pursuit of derisking may also have unforeseen and potentially undesirable consequences.

A derisking strategy could reduce a pension scheme’s investment risk, but actually increase its risk overall.

Loss of returns

For example, imagine that a scheme’s long-term objective is to achieve self-sufficiency within 10 years, with 70 per cent of its assets invested for growth.

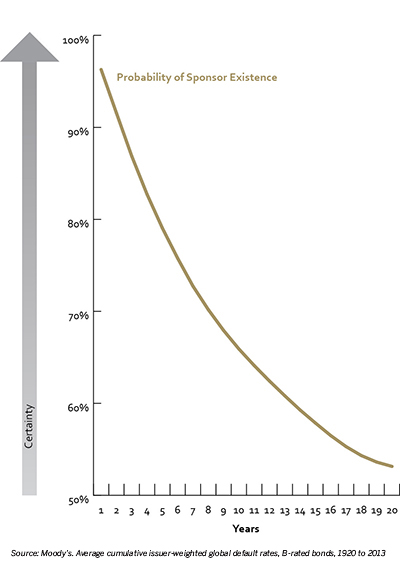

The further into the future we look, the less certain we can be about the ability of the sponsor to repair any deficit

It then decides to employ a derisking strategy, by which the allocation to growth assets is reduced gradually, over time, to 10 per cent.

Correspondingly, its allocation to bonds grows from 30 per cent to 90 per cent.

This should reduce the volatility of its funding level. However, a lower allocation to growth assets will reduce its expected return.

That means the long-term objective of self-sufficiency within 10 years will no longer be achievable. In fact, it’s going to take twice as long.

And that means the scheme will be reliant on its sponsor for an additional 10 years – and the further into the future we look, the less certain we can be about the ability of the sponsor to repair any deficit.

As a result of it's derisking strategy the scheme has increased its covenant risk, the danger being that its sponsor may be unable to make up for any deficit the scheme may have.

So akin to our yoghurt example, where we thought we were reducing risk, we may have simply been exchanging one risk for another.

Maybe we should take a broader view. For an individual, a full-fat yoghurt can be healthy as part of a well-balanced diet. For a pension scheme, a degree of risk can be embraced in the pursuit of rewards, provided it is part of an integrated approach to risk management.

The key is to remove risks where they cannot be tolerated. Risk management tools such as diversification, dynamic asset allocation and liability hedging can assist you in striking the right balance.

Danielle Jacques is associate director at consultancy P-Solve

Most Viewed

- What does Labour have in store for the pensions industry?

- LGPS latest: GLIL backers invest £475m for UK infrastructure push

- Dashboard costs rose by 23% in 2023, figures show

- Border to Coast launches UK strategy in major private markets push

- How the pensions industry can better support people with mental health problems