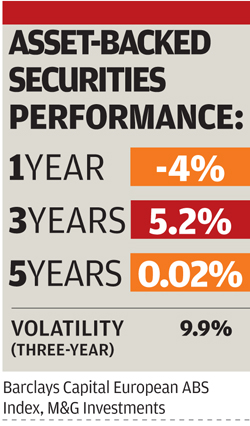

Investment snapshot: asset-backed securities

Asset-backed securities (ABS) could be the most misunderstood of fixed income investments –shunned by some for their complexity, lionised by others for their robustness, they divide opinion.

For pension schemes, the best can be as secure as some AAA-rated government bonds.

In their purest form they are bonds issued by banks for funding reasons – just like covered bonds or unsecured debt.

However, unlike many types of bank debt, an ABS offers its investors something much more secure – access to a ringfenced pool of assets that sits off the bank’s balance sheet. If the bank fails, the asset holder gets an early claim on this collateral.

These assets are loans made by the bank and they come in four main asset types: residential mortgages, commercial mortgages, credit cards and car purchases. Mortgage loans make up the vast majority of the ABS market.

An ABS offers its investors something much more secure – access to a ringfenced pool of assets that sits off the bank’s balance sheet

They usually also provide an income linked to interest rates – not bad at a time when rates sit at historic lows and pension funds are mindful that this will change at some stage.

Understanding these bonds can take time. An investor in a residential mortgage-backed security issued by a UK high street bank must measure the bank’s stability and solvency, the underlying assets and the way in which these assets are structured. They will tend to be grouped into tranches according to their credit rating – AAA, AA, BBB, and so on. These rankings come from credit ratings agencies but sensible investors will want to do their own analysis. This may even include the creditworthiness of individual mortgage borrowers in the loan pool.

The worst ABSs do not have such good track records. In the run-up to the credit crunch, many investors piled into US subprime mortgage-backed bonds. They were confident in the attractive ratings bestowed on them by ratings agencies without looking too closely at the underlying loans.

When these subprime mortgage borrowers started to fall behind on their payments from around 2007, and when some bonds started to fail, many investors marked the whole ABS sector as tainted, dropping all their holdings regardless of credit quality. They even shunned European ABSs despite the markets displaying few of these issues.

Those who could identify securities issued by stable institutions and with good quality collateral could pick them up remarkably cheaply.

In some cases these bonds were beaten down to 40p or 50p in the pound. It really was a once-in-a-lifetime investment opportunity.

Capital values on these better ABSs have pretty much returned to par, but when pension schemes need secure income streams to match their liabilities, the argument for holding them persists.

Bernard Abrahamsen is head of institutional distribution at M&G Investments

Most Viewed

- ‘A fundamental point of fairness’: MPs call for action on discretionary increases

- TPR to scrutinise ‘systemically important’ professional trustee firms

- What does Labour have in store for the pensions industry?

- Defining the role of the scheme actuary

- What CalSTRS’ data problems mean for pension funds’ climate goals