Discount rates and denial: Will local authorities soon see pension costs rise?

The last couple of Budgets have focused on freedom and choice, but March brought a little surprise for the public sector, and it is one it would probably have preferred to do without.

George Osborne announced plans to revise the discount rate used for public sector pension schemes from consumer price index +3 per cent to CPI +2.8 per cent as part of a bid to improve the state of public finances.

Actuaries are conservative, and while there may be headroom between their own assumptions and state rates, they are likely to include the government’s position in their considerations

“To ensure those pensions remain sustainable, we have carried out the regular revaluation of the discount rate and public sector employer contributions will rise as a result,” said Osborne.

“This will not affect anyone’s pension, and will be affordable within spending plans that are benefiting from the fiscal windfall of lower inflation.”

Individual pensions may not be affected now, but it could have considerable repercussions for a number of public sector schemes.

What’s going on?

There is nothing sinister in the timing of the move – it comes as part of a scheduled five-year review since the the last discount rate was set in 2011.

But according to Budget documents, the impact could come in the shape of additional employer contributions to the tune of £2bn a year from 2019 among unfunded public sector pension schemes such as teachers, civil servants, NHS and the police and fire service.

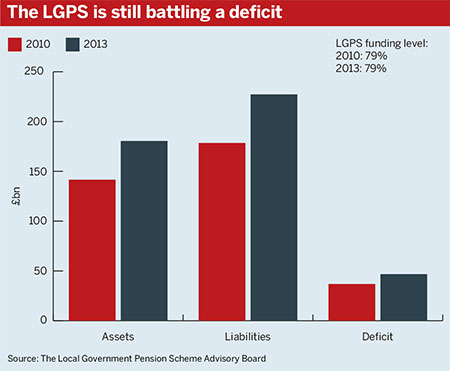

In theory, the funded Local Government Pension Scheme, which operates a triennial review system, will not be affected. However, while not immediately apparent, there are implications for the LGPS, says Mike Allen, managing director of the London Pensions Fund Authority.

Calculations relating to cash equivalent transfer values both in and out of the scheme have been put on temporary hold while the Government Actuary’s Department produces new tables.

“Ultimately, this change is likely to result in higher transfers being paid out of the LGPS and smaller credits being given on transfers-in from certain schemes,” says Allen, but adds it is a short-term measure.

More to come

The real impact may come from the effect the ‘superannuation contributions adjusted for past experience’ discount rate will have on the key performance indicators and section 13 (Public Sector Pensions Act 2013) valuations applied to the scheme as a whole, he says.

Once the National Scheme Advisory Board has collated the 2016 valuation exercise results from LGPS authorities, it will review the deficit management and contribution levels against agreed KPIs.

“The results of such a review could lead to a greater number of authorities or employers failing to meet the tests laid down and therefore being required to review the levels of contributions payable by employers in order to meet the test,” says Allen.

There are four core KPIs considered by NSAB: risk management; funding levels and contributions; deficit recovery; and required investment returns. Three of these include direct reference to the SCAPE financial assumptions.

Not just a public sector problem

The consequences of any change extend beyond the public sector, says Robert Plumb, an independent public sector consultant.

“Lots of employers on those schemes – and there are thousands of them – are in the private sector. They will also be affected when costs increase from lowering the discount rate, albeit in about three years’ time.”

Not everyone agrees the discount rate change will have any lasting influence on how the future rates for LGPS employers are assessed.

“This is very much a second order issue,” says Paul Middleman, a partner at Mercer. “It’s not going to be a major influence at this stage.”

The reason for this is because employers in the LGPS use their own commercial actuarial firms to undertake valuations and assess risk profiles and strategies.

But Plumb believes the chances of independent actuaries being influenced as a result of this change are strong. There are only four firms dominating the public sector market – Aon, Barnett Waddingham, Hymans Robertson and Mercer – and their assumptions are not going to be wildly different.

“Actuaries are conservative, and while there may be headroom between their own assumptions and state rates, they are likely to include the government’s position in their considerations,” says Plumb.

Hymans Robertson actuarial partner Barry McKay concedes that actuaries’ assumptions may be influenced by the government’s change. After all, if it reflects a view on the growth of GDP, this would affect the returns and would have a place in the valuation process, he says.

Plough your own furrow

But that does not mean actuaries are going to place extra stress on this change in their valuations, says McKay. The NSAB is looking for a consistency of approach in the valuation among the actuaries valuing the LGPS, but despite differences apparent between firms, what exactly consistency means is moot.

“At times we will have very different outlooks on the market and our assumptions will be tailored to different employers and even individuals with different employers,” says McKay.

There is good reason for doing so as longevity can be tailored to fund and region. For instance, there is a clear variance in longevity between members working in Glasgow and those in the south of England; and there are other demographic factors to consider.

“Member experience is an important factor,” adds McKay. “So this is more useful than applying a one-size-fits-all assumption to an employer.”

“These are legitimate reasons for bespoke valuations that produce differences in valuations and the assumptions used to calculate them.”

Elephant in the room

This change comes at a time when unions such as Unison have been making a case for greater contributions from employers, although this might be driven more by politics than deficit management, says David Davidson, a director at consultancy Spence & Partners.

“There are questions about whether Osborne is pushing additional cost onto the scheme in order to encourage the debate about defined benefit pensions in the public sector,” says Davidson.

Of course, he adds, if and when an LGPS merger goes ahead, schemes will likely be all on the same basis. But in the meantime, if actuaries seek to make a change to the discount rate, this is going to have to be negotiated with employers and unions.

Only time will tell if the change to public sector scheme discount rates will influence those setting rates for LGPS employers.

If they should be forced downwards, we will soon hear of it, as the immediate impact will almost certainly be a cut to frontline services from local authorities who are already juggling huge deficits.

Most Viewed

- ‘A fundamental point of fairness’: MPs call for action on discretionary increases

- TPR to scrutinise ‘systemically important’ professional trustee firms

- What does Labour have in store for the pensions industry?

- Defining the role of the scheme actuary

- Five themes at the forefront of a sustainable future