Decoder: will reforms get results?

To achieve a comfortable retirement, we are expected to save a percentage of our wages that will make for an uncomfortable present. Charlie Thomas asks whether a realistic solution can be found.

John Ralfe caused uproar last Monday when, speaking on Radio 4’s Today programme, he said: “My rule of thumb is you need to be saving 25% of your income… some of that may come from your employer… people might say that’s totally unrealistic, but the minimum amount under auto-enrolment just isn’t enough.”

A stream of tweets followed on the twittersphere, largely decrying the “silly” and “impractical” idea of saving a quarter of your income towards retirement.

More worrying though is the 22% of workers who are saving nothing at all

Take the average earner, who takes home £25,000 a year before tax.

Even if their employer was generous, and offered to put 5% into their pension, the chances of the employee being able to save £5,000 into their retirement savings are nigh on impossible when you take student loan repayments, income tax, national insurance contributions, rent/mortgage repayments, utility bills and transport costs into account.

If 25% is completely unacceptable, what contribution rates should we aspire to ahead of auto-enrolment?

Once the regulations are in full swing, the minimum contribution by law will be 8%, but it’s widely recognised this will fall short of providing what most people believe to be an acceptable retirement income.

Figures from the Office for National Statistics’ 2010 Pensions Trends report showed it was difficult to get an “average” contribution rate, since the numbers varied sector by sector.

For example, the majority of those in the 20-29 bracket in private sector defined contribution schemes put away between 4% and 8%, whereas the majority of those aged 30-39 from the same category save between 8% and 12%.

It’s impossible to say how much you need, but it is important to get started

Compare that with employees from professional, technical and scientific, healthcare and admin support employers, and the vast majority put away 12% to 15%.

The average total contribution to occupational DC arrangements in 2009 showed slightly more than 6% coming from the employee, with around 5% offered by the employer.

The Pensions Policy Institute recently suggested 15% of salary might be a more realistic figure, although according to Scottish Widows’ most recent retirement report, the average

savings ratio is still well short of that – at 8.9%.

More worrying though is the 22% of workers who are saving nothing at all.

Simplifying the message

Speaking at a recent National Employment Savings Trust, event Tom McPhail, head of pensions at Hargreaves Lansdown, suggested that telling the public to put £1 away for every £10 earned might be an easier message to swallow.

Strangely, employees also had an overwhelming preference for increasing contributions by an even number, rather than an odd one

Meanwhile, Andy Cheseldine, principal at LCP, says a realistic amount depends on the individual’s income, other expenditures, how much the employer will contribute and other outgoings, such as student loan repayments.

Other contributing factors include retirement expectations after accounting for state benefits, other sources of income they might expect, such as an inheritance, and assumptions on investment growth.

“In short, it’s impossible to say how much you need, but it is important to get started,” Cheseldine says.

“The key criteria are – recognising sometimes they are mutually exclusive – don’t starve, don’t get into debt just so you can save somewhere else, and make the most of matching from an employer.”

Food for thought

Standard Life’s Keep On Nudging report, released last autumn, found that of those people who said they would remain enrolled when auto-enrolment is introduced, 31% said they would agree to their contributions rising with pay increases, and would also be willing to make additional voluntary contributions on top of this.

Strangely, employees also had an overwhelming preference for increasing contributions by an even number, rather than an odd one.

For the median-earning 25-35 year old, increasing contributions by an additional 4% of earnings would add £135,000 to their pension pot, making a material difference to their retirement income.

But a median earner saving 4% is likely to achieve a pension of just 45% of pre-retirement income. It’s clear there’s a long way to go if we’re to achieve successful DC schemes.

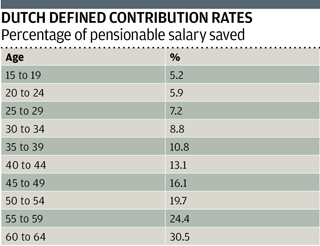

As a final thought, a Dutch reader got in touch to offer an explanation of how DC schemes work in the Netherlands.

Their defined contributions are limited by the tax office. Most companies use the numbers below to determine their contribution levels.

There are some slight variations, and the numbers are based on a percentage of pensionable wage (which roughly means the amount of salary exceeding €12,000 a year), but by and large, the table illustrates the combined DC rates.

Charlie Thomas is special projects editor

Defined ambition or guaranteed poverty?

Six months from the introduction of auto-enrolment into what will almost universally be defined contribution arrangements – notably Nest itself – pensions minister Steve Webb has taken a sideswipe at DC and implored the industry to do better.

It seems he would like people to have more certainty about what they’ll get in retirement.

Possible ways to do this include guaranteeing the payout but not the pension, or plans where a guaranteed benefit is payable on a variable date depending on market conditions.

What, after all, would you prefer? To be certain of getting a pension of 10% of salary, or the uncertainty of a pension that could be between 15% or 25% of salary?

Ignoring the obvious point that neither of these approaches really deliver certainty at all, we need to consider whether the pensions minister is really asking the right question.

What, after all, would you prefer? To be certain of getting a pension of 10% of salary, or the uncertainty of a pension that could be between 15% or 25% of salary?

Nobody wants to be certain that they’ll be poor, but there is a concern this is what defined ambition (DA) will deliver.

The costs of guarantees and the clear lack of interest among corporate Britain in underwriting pension promises means any DA pension wou

ld be set at a low level.

We believe the right question to ask is how can DC deliver better outcomes. It’s not rocket science – there are six key steps:

- Increased take-up and ensure people stay joined;

- More contributions – use matching structures, Save More Tomorrow and other ‘nudge’ tactics to encourage members to increase savings rates;

- Investing well – make sure members are invested in a way that not only maximises their benefits but ensures they can be more certain of what they’ll get as retirement approaches;

- Efficient administration – processing of contributions and benefits should be robust and accurate. Any errors should be made good quickly;

- Good communication – engage consumers in outcomes, but don’t try to make them pension or investment experts. Most are just not that interested;

- Better retirement incomes – make shopping around the default, to secure the right income at the right price.

Of these factors, contribution levels are perhaps the most critical of all.

Having invested so much energy in getting people into well-designed, cost-effective pension plans, we then also need to get them funded properly.

We can’t expect employers to do this on their own. Rather than dreaming up complex guaranteed products that will more than likely confuse and disappoint, let’s focus single-mindedly on persuading consumers to save more.

That’s the best way of fulfulling ambition.

Richard Parkin is head of proposition, DC and workplace savings, at Fidelity Worldwide Investment

Most Viewed

- What does Labour have in store for the pensions industry?

- LGPS latest: GLIL backers invest £475m for UK infrastructure push

- Dashboard costs rose by 23% in 2023, figures show

- Border to Coast launches UK strategy in major private markets push

- How the pensions industry can better support people with mental health problems